Al-Monitor — Last year’s deadly protests in Iran over the death in police custody of a young Kurdish woman, Mahsa Amini, have cast a pall over the country’s vibrant art scene, with many galleries in Tehran temporarily shuttered amid fears of drawing the ire of protestors and authorities alike.

Even as they reopen, business remains shaky and gallerists continue to seek ways to sell works in overseas markets, notably in London and Dubai, in order to stay afloat. A slew of fresh US sanctions in 2019 under then-President Donald Trump had already dealt a blow together with a saturated market for Iranian art. The Iranian government does little if anything to promote its own, viewing artists with suspicion in the best of times.

In this challenging atmosphere, Iranian artist Bita Ghezelayagh is making a name through her exhilarating fusion of ancient Iranian crafts with universal themes of rebellion, hope and alienation that are permanently displayed in the British Museum, the Victoria and Albert Museum, the Jameel Foundation in Saudi Arabia and other signature venues worldwide.

Her most recent work, which fronted “The Resistance of Pen and Paper” — an all-star exhibition at the blue-chip Richard Saltoun Gallery in Mayfair, London — targets censorship in her home country.

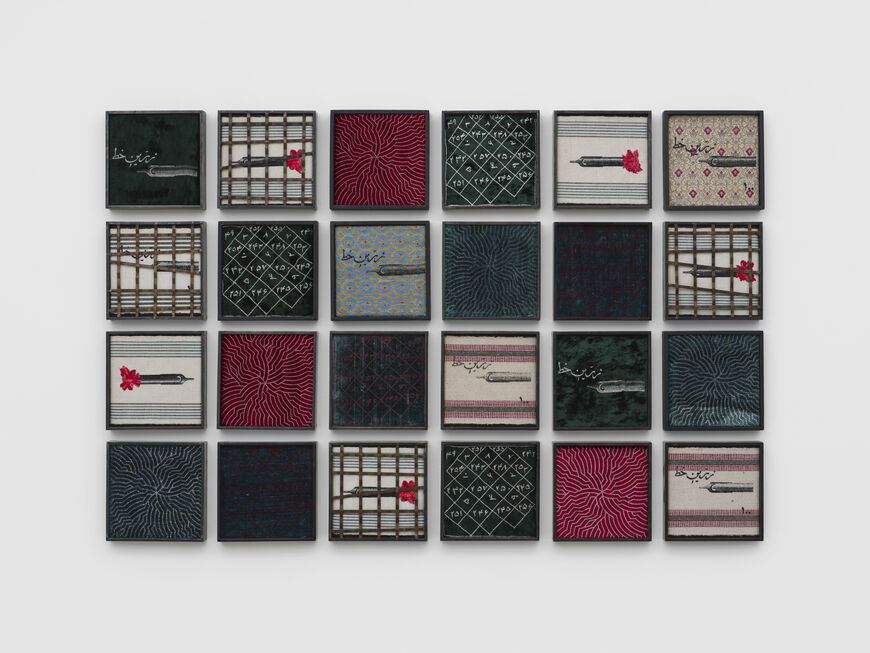

Fountain pen nibs that she was entreated to buy in the hundreds by an antique dealer in Tehran are encased in glass — at once shielded by it and bursting to shatter it — in an installation called “Encapsulation.” “Pens and Roses” features 24 framed squares of vintage velvet and brocade arranged in a rectangle. The nibs are printed on them, with pink roses jutting from their elongated barrels evoking it would seem her fellow artists’ sugarcoating of criticism to avoid the regime’s prisons.

“You always feel that what you do will cause trouble. As an Iranian you always worry,” said Ghezelayagh during a recent interview over tea and Persian delicacies in her flat in London. Born to an architect father and a lawyer mother in Florence, she returned to Iran at age 5 to witness the 1979 Islamic Revolution that brought the clerical regime to power. An angry mob descended on her family residence in northern Tehran — home to the moneyed, the powerful and old families such as hers. Her father’s reputation for probity as project manager of Ekbatan, the biggest residential complex in the capital, spared them the fate of many of their neighbors. But fear and instability remained a constant as the Iran-Iraq War erupted. “We had to hide in basements. Food was restricted. The country was very black,” she recalled.

A felt tunic by Ghezelayagh stitched with tiny metal keys “to heaven.” (Photo courtesy of the artist)

The unremitting wail of sirens followed by loud explosions spurred the young girl to seek refuge in the works of Persian literary icons such as Omar Khayyam, Nizami and Ferdowsi. “My work is very much based on literature. My creativity is a shield.”

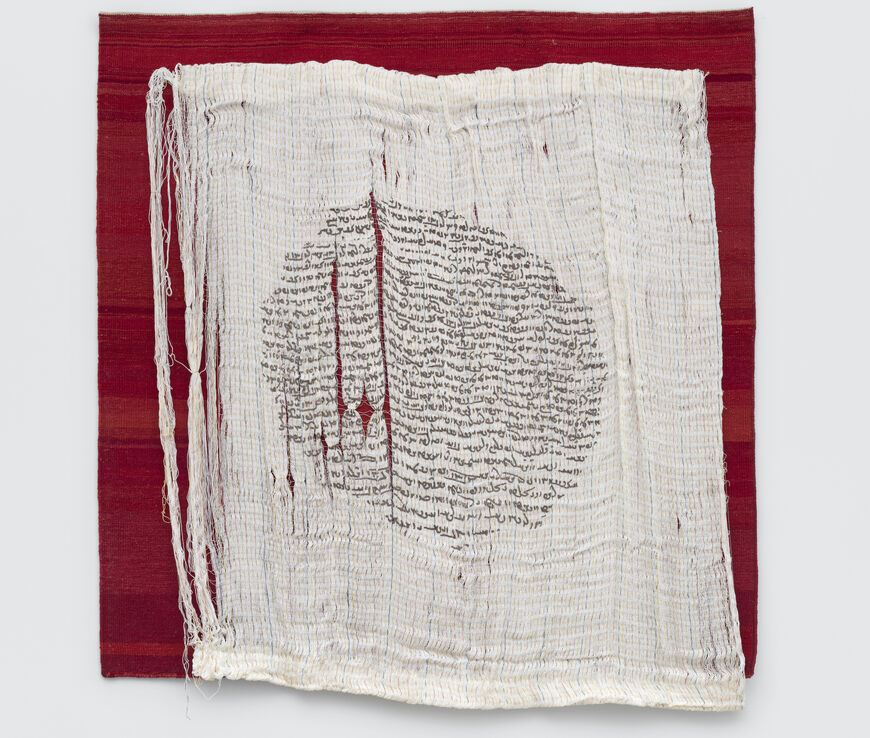

Ghezelayagh’s compassion for the estimated half a million Iranians — many of them boys — who perished in the eight-year-long conflict emanates from her early work. Hundreds of tiny metal keys “to paradise” and tulips symbolizing martyrdom that would be pressed into the hands of soldiers ahead of combat are sewn on to felt shepherd’s cloaks together with tags imprinted with the face of Hossein Kharazi, the fabled war hero who was killed in the siege of Basra in 1987. The cloaks were shown in her first-ever solo exhibition, “Felt Memories,” which took place in London in 2008.

Ghezelayagh’s passion for felt was born during a trip to Lorestan province in western Iran where she was smitten by a shepherd’s cape hanging forlornly from a shop ceiling.

“In Iran, felts are used as doormats, as floor covering in opium dens,” she said. She elevated them to an art form, pouring at once the pain and beauty of her troubled nation onto their rough surfaces and restoring dignity to their makers through her collaboration with local craftsmen and Afghan embroiderers sheltering in Iran.

Planet Sun (2022), Bita Ghezelayagh. (Photo courtesy of Richard Saltoun)

“This return to craft is something that the great artist of the earlier generation, Parviz Tanavoli, also does,” observed Venetia Porter, honorary research fellow at the British Museum and its former curator of Islamic and Contemporary Middle Eastern Art. “It’s a demonstration I think of a passion for Iran and its cultures and using material culture to tell new and contemporary stories. In the case of Bita, the felts cleverly make those political allusions while making something beautiful and innovative at the same time,” Porter told Al-Monitor.

Be they carpet fragments reimagined as medieval tunics or a Japanese kimono belt draped over canvas, Ghezelayagh’s training as an architect in France in the footsteps of her beloved late “Papa” is evident in the unstinting precision of all her works. Even the looseness of her calligraphy — it’s never the central focus — is deliberate.

Her eye for composition developed as a set designer during the filming of the widely acclaimed “The Pear Tree,” which launched the career of the world-famous Iranian star Golshifteh Farahani. The 1988 drama dissecting Iran’s bourgeoisie was written and directed by Iran’s celebrated filmmaker Dariush Mehrjui. He was stabbed to death in October together with his wife in their Tehran home. “It is incomprehensible,” said Ghezelayagh, whose name means “foot of gold” in Azeri Turkish that is spoken in Iran’s northwestern region.

When she returned from Paris, “What I saw was a very pure country. We had no advertising, no tourists. We were disconnected from the outside world. I found its beauty touching and fascinating. It was a feast,” Ghezelayagh said. Casting her gaze across Iran both as a native and an outsider, “She is bringing into the conversation something of the moment,” noted Aria Amaya-Akkermans, a contemporary art researcher based in Italy who writes frequently for leading art magazines.

“She is not only trying to preserve what was forgotten, she is making these materials part of cosmopolitan history, she is giving them sculptural form in a very poetic way,” Amaya-Akkermans told Al-Monitor. The core of the modern world of literature, art and philosophy is the product of long-distance travel. “Unlike many contemporary artists who are pigeonholed as Middle Eastern, Bita conveys that. She is different. She is very collectible,” he added.

“Pens and Roses” features 24 framed squares of vintage velvet and brocade arranged in a rectangle. (Photo courtesy of Richard Saltoun)

It is, therefore, unsurprising that high-end Western gallerists like Saltoun are showing Ghezelayagh’s work. “It’s a really big deal,” Porter said. The artist, who splits her time between London and Tehran, says that her next project is centered on water and glass and “something about the moon.”

Ghezelayagh seems almost disbelieving of her own success as she speaks of her “gratitude” to Saltoun, even as big-name private collectors such as Sara Ali Reza of Saudi Arabia and Mohammed Afkhami snap up her works. Perhaps it is rooted in her own government’s refusal to acknowledge her talent and display her work in national museums. There is an ever-present tinge of sorrow in Gezelayagh’s gray-flecked green eyes, which deepens when the subject is raised.

“I always feel so lonely,” she acknowledged. “Because of the constant upheaval in my country, the past has been taken away from me. But I refuse to be a victim.”

Shabtabnews In this dark night, I have lost my way – Arise from a corner, oh you the star of guidance.

Shabtabnews In this dark night, I have lost my way – Arise from a corner, oh you the star of guidance.