Iranwire – IranWire interviewed Professor Anthony Feinstein about the psychological impact of eye injuries and other wounds sustained by anti-establishment protesters in Iran. A psychiatrist at the University of Toronto, Prof. Feinstein has ample experience in studying the effects of trauma on mental health. He previously worked with IranWire to research the impact of trauma on Iranian journalists who face the threat of persecution and even torture in their line of work.

In this latest study, he investigated how symptoms of depression and post-traumatic stress affected protestors injured in demonstrations, as well as non-protestors and those who were not physically harmed. He initially expected eye wounds — profoundly grievous injuries which can fundamentally change how a person interacts with the world — to result in the greatest levels of trauma. But, perhaps because of the moral courage these wounds have come to represent, he found the opposite.

***

It’s been more than a year since the death of 22-year-old Mahsa Amini in police custody ignited protests across Iran. Demonstrators still chant “Woman, Life, Freedom” at rallies against a brutal government that continues to maim and persecute its citizens.

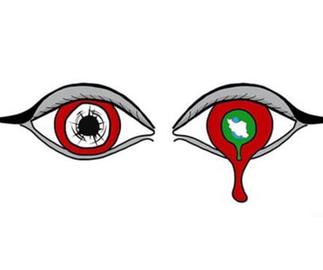

Countless Iranians were injured and even killed by security forces as they were speaking out against the Islamic Republic. Eye injuries caused by metal pellets, shrapnel and beatings have become a hallmark of this state violence, a systematic means of repression IranWire has been documenting for months.

These wounds are especially cruel, inflicting pain long after the initial injury and, in many cases, completely changing the way a person interacts with the world around them.

Although individuals can develop powerful coping methods, losing sight in one eye can have a greater psychological impact than losing a limb.

And losing sight in both eyes can be devastating, as ophthalmologists told IranWire earlier this year.

Anthony Feinstein, a professor of psychiatry at the University of Toronto, has been studying the psychological impact of injuries among Iranian citizens to better understand the ways this trauma continues to bleed into their lives.

Before he began, he thought those who sustained grievous injuries would have experienced the greatest psychological consequences.

But he found the opposite while conducting his research. Protesters with eye wounds, he told IranWire, had markedly lower rates of negative psychiatric symptoms than those with other types of injury.

Quantifying Psychological Injury

Prof. Feinstein surveyed 94 Iranian citizens, many of whom had been injured in protests. He used validated questionnaires to quantify symptoms of depression and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). He also asked participants how they felt now about their role in the anti-establishment protests.

His surveys scored participants according to these psychiatric symptoms and asked how individuals felt about their involvement in the protests and whether they felt they were being surveilled by the state, for example.

The purpose of the survey was not to diagnose depression or PTSD, but to understand how common and how severe the symptoms of these illnesses were among the cohort.

Among the participants, 63 had been involved in protests while 31 had not. Just over a third of the protesters had been wounded (36), and 14 of these had serious eye injuries. Thirteen had lost sight in one eye and one had tragically been fully blinded.

Of the non-protesters, nine were wounded, with two having experienced eye injuries.

Several participants in both groups reported having friends and family members injured, in the eyes and elsewhere, or even killed in the monthslong, largely peaceful protests.

Symptoms of depression can include things like a sad mood, irritability, an inability to enjoy things, disturbances in sleep, changes in appetite, reduced energy, feelings of despondency, low self-esteem, fatigue, inability to concentrate and, in severe forms, suicidal thinking.

PTSD, he explained to IranWire, is a condition that can arise in response to extremely stressful events. “An overwhelming stress,” he said, “or a kind of event that could have killed you or killed other people.”

It can result in a range of symptoms that fall into categories such as intrusion, arousal and avoidance.

Intrusive symptoms are those which involuntarily enter a person’s consciousness: nightmares, flashbacks and unwanted recollections of sights, smells and memories, Prof. Feinstein explained.

Avoidant symptoms are a response to these intrusions. These are attempts an individual might make to avoid reexperiencing a traumatic event: conscious efforts “to try and distract yourself or to block out recollections.”

Arousal, on the other hand, refers to an overly excitable nervous system, whereby a person may find it hard to concentrate or to fall asleep, and may find themselves more irritable. Even when an individual returns to a safe place, Prof. Feinstein explains, “I’m looking over my shoulder because I think I’m under threat.”

PTSD can also leave people with an exaggerated startle response that’s sustained long after a traumatic event. “In response to a slight noise, you react excessively,” he added.

Prof. Feinstein didn’t find any overall difference in psychiatric symptoms between the protestors and non-protestors who answered his surveys.

But interesting and surprising results emerged among those who had been wounded, a group that experienced high rates of both depressive and PTSD symptoms.

In contrast to his expectations, those with eye injuries experienced significantly less depression and fewer intrusive and arousal-related PTSD symptoms than those with other kinds of wounds.

“Striking” Results despite Limitations

It’s important to note that Prof. Feinstein’s research has several limitations. For example, the sample size is relatively small, while many thousands of people have been involved — and injured — in protests across Iran over the last 12 months. So, it’s impossible to know how well these results track against protesters in general.

It’s also hard to know how they compare the Iranian population overall, which may have different baseline levels of psychiatric symptoms than other, better studied, countries.

Prof. Feinstein was also unable to speak to participants in person — something that could provide much richer opportunities to assess a person’s mental state and understand why they feel the way they do. And although he asked questions about participants’ experiences outside of protests, the study did not assess what other factors could explain their psychiatric symptoms.

“Nevertheless,” Prof. Feinstein said, “Even with those disclaimers, what is striking is that what started out as my a priori hypothesis that a group that was blinded would be in the greatest psychological difficulty turned out to be wrong.”

The study will leave many readers wondering why these individuals might be so resilient in the face of life-changing violence?

The research was not designed to offer a causal explanation for such findings, so it’s impossible to know for sure why this group seemed to experience a lower level of psychiatric injury.

But Prof. Feinstein suggests the concept of moral injury — as well as the way eye injuries are viewed among protestors — may shed light on the matter.

Moral injury, he said, can arise “from witnessing, perpetrating or failing to prevent” immoral acts. “Had they kept quiet? Had they done nothing? They could have felt a sense of moral failure by their silence,” he said.“The fact that they made a stand and spoke out or protested meant that moral injury for them doesn’t enter the equation.”

It makes sense that an individual participating in protests, “even though it came with awful consequences for themselves,” would view their involvement “as an act of moral courage,” he said.

This might mitigate some of the trauma symptoms they might otherwise experience following injury.

The answer to one of Prof. Feinstein’s survey questions — how individuals feel about their involvement in the protests — may help explain why those with eye injuries specifically appeared to experience less severe psychiatric consequences.

Every protestor who sustained an eye injury — in comparison to 77 percent of those who sustained wounds in other parts of the body — said they viewed their involvement in the protests in a positive light.

Eye injuries are considered by many protesters as a symbol of resistance against the regime. Eyes are believed to be a deliberate target for security forces so, despite the grievous nature of these wounds, they may become a particular source of pride for some victims.

Take 34-year-old fitness instructor Mercedeh Shahinkar, who lost most of her sight in one eye during protests. She described the injury — which still caused her pain months later — as “a badge of honor.”

Similarly, 29-year-old psychologist Raheleh Amiri, said of her own injured eye: “These days, when I look in the mirror, my right eye is much smaller than the left one but, to tell the truth, I am in love with my right eye because it glows with honor.”

Protesters around the world have held up posters of Elaheh Tavakolian, who lost an eye during protests, with a white heart over the injury.

And as 23-year-old Ali Zare, who also lost his right eye during protests, stated on social media: “My eye for a free Iran.”

An eye wound may serve as a marker of having “stood up in protest,” Prof. Feinstein said. “It means you can look yourself in the face in the morning and say, I never kept quiet.”

But for now, he added, this remains “just a theory” outside the scope of his research project.

Surprising results like this, he added, are “why we do research.” Assumptions can be “completely overturned by data. And this is what’s happened over here.”

Shabtabnews In this dark night, I have lost my way – Arise from a corner, oh you the star of guidance.

Shabtabnews In this dark night, I have lost my way – Arise from a corner, oh you the star of guidance.