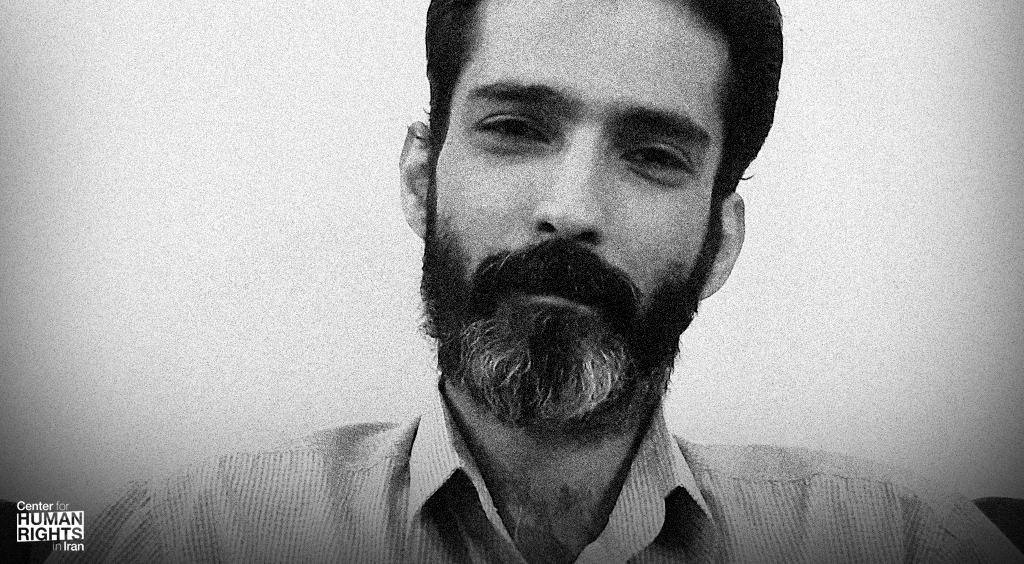

CHRI – Human rights lawyers in Iran are a crucial lifeline for individuals accused of crimes against the state—yet they’re few and far between. For decades, the Iranian government has been working to eliminate independent lawyers through various tactics, including harassment and imprisonment. “What the state is trying to do to lawyers is shameful,” Amirsalar Davoudi, a defense attorney who knows this story all too well, told the Center for Human Rights in Iran (CHRI).

Back in June 2019, the same year Davoudi was granted the Human Rights Award by the Council of Bars and Law Societies Of Europe, he was sentenced to 111 lashes and 30 years in prison, of which he must serve 15 years. The sentence was for the charge of forming “an illegal group”—a news channel for lawyers on the Telegram messaging app. Davoudi was imprisoned until recently, when he was allowed to go home on furlough (temporary leave), which could end at any time.

Davoudi is but one of many human rights lawyers who have been harassed, threatened, suspended or banned from work, arrested, and unjustly imprisoned by the authorities in Iran. Despite the constant threat of re-imprisonment hanging over his head, he remains committed to defending and promoting human and civil rights in his country: “We must convey human rights principles to society in the shortest possible time and when people become aware, then society itself will step into action.”

CHRI: What are the characteristics of a human rights lawyer in Iran?

Davoudi: Ever since human rights became a primary topic in foreign policy matters of the Islamic Republic of Iran… there has never been an organized and logical approach to dealing with human rights issues. Whatever that has been accomplished amounts to personal experiences of individuals who are active in this field.

Of course, in the early 2010s, for the first time Iranian universities added human rights to their curriculum as a separate branch in legal studies. These schools include Shahid Beheshti, Allameh Tabataba’i, and Tehran universities. But like all new subjects in Iranian universities, it will take time for it to take root and form connections in society.

That aside, the ruling establishment continues to resist demands for human rights, especially when it regards them as part of the Western paradigm. As an ideological state, the Islamic Republic considers itself as the guardian of new, positive, and practical ideas on human rights. So, there is this friction between the official view on human rights and international principles.

In my opinion, a human rights lawyer is not working exclusively on security and political cases. Some lawyers are active in other fields, such as the environment, children’s rights, women’s rights, ethnic minorities, the LGBT community, and many others. These are all areas that are tied to our future as individuals, and therefore in the jurisdiction of human rights lawyers.

Human rights lawyers in Iran try to work within existing laws, not because they approve or disapprove of them, but because they are obligated to use existing potential in the law to defend people’s rights in various places, whether in court or in legal discourse and criticism.

CHRI: Can a human rights lawyer be considered an activist when directly challenging the state for its rights violations?

Davoudi: In the final analysis, I do not consider a human rights lawyer to be the same as a human rights activist. I think human rights lawyers are those who are in some fashion engaged with the judicial system. Under the general umbrella of human rights, we can separate specific categories, such as the legal profession, or in other words, human rights lawyers. They can be engaged in the field of human rights through the media, research, or even activism.

CHRI: What are the main obstacles facing human rights lawyers in Iran?

Davoudi: I want to discuss this from the perspective of the people living under the Islamic Republic. There is no doubt that the ruling establishment has made the strongest effort to fortify its ideological foundations and create many obstacles for human rights activities. But can the people play a role in pushing the state towards observing human rights? I think they can.

I have no intention of absolving the ruling establishment but, in all fairness, I want to ask, have we used all available paths to confront state policies? I have my doubts. For clarity, allow me to give you an example. When we study the street culture in Iran, we see that the biggest insults and jokes are still centered on personal opinions.

A political and civil rights activist recently posted a personal photo on social media, which in the opinion of many, was an insult to religious symbols. Then people posted insulting comments under the photo. I am certain that some of them were cyberspace agents of the state. I consider these kinds of comments an important social phenomenon. Many of the insulting comments against the person who posted the photo are serious indications of a crisis in human rights. In other words, respect for the views of others, as well as insults toward religions or ethnic minorities, are part of our national culture that arise from the people. They show us where our culture is heading. What does it mean when so many people curse about someone’s sexuality?

The state has certainly failed in its responsibilities and we can blame everything on the officials for their wrong political and cultural policies and lack of spending on the right cultural policies. Officials boast about unprecedented spending on religious schools and mosques, and they control the state radio and television. They control every aspect of cultural life in the country. But the outcome has been very bad. At the same time, however, we must allocate some of the blame to the people themselves. Are we, as people, forever going to disrespect the views of others with the excuse that the state has not educated us on human rights?

When the authorities want to execute someone who committed murder as a juvenile, we challenge them and ask why. They say, because he committed murder and used his own will to do it. But what about the cultural, economic, and genetic factors that contributed to the crime? So, we do criticize the state’s position. On the other hand, we must also accept that our collective will is not respectful of human rights the way it should be.

CHRI: What should people do if the state is not committed to improving human rights?

Davoudi: We need to reassess our strategies and methods. We are dealing with a state that is not prepared to respect the rights of the majority of the people. We cannot work with this state. Things have gotten to a point where it does not care at all about these issues. If we are unable to force the state to change and reform itself, we need to find other solutions; solutions that involve the people and groups that share certain principles and wishes. To make this happen, activists have social media as a very important tool. To be on the right track and find new solutions, we need to critique previous methods.

For years, we have been utilizing the media but not in the correct way, in my opinion. The reason is that our media output has lacked quality. For example, the media use the most sophisticated visual methods to produce commercials to help sales of tomatoes and other products, but they won’t make the same effort to present human rights as an important component of society. We must find every way to win people’s hearts. Naturally, when we are dealing with people and want to make them aware of their rights effectively, we need to deploy soft methods, as opposed to the state’s violent and oppressive tactics.

We must first try to identify various sectors in society and distinguish their religious, ethnic, and generational differences, as well as their social class and level of education. We cannot address society as a homogenous group. We must convey human rights principles to society in the shortest possible time and when people become aware, then society itself will step into action. Look at how teachers are demanding their rights on the streets every day. Their common issue is economic. What began organically has turned into a serious force to demand teachers’ rights. However, we have not been able to achieve the same in turning human rights into a vital and important element among all sectors of society.

The second issue is fairness. Some human rights activists have bemoaned and criticized the state without achieving anything. They have been influenced by political trends and changed their positions and methods. This has not been helpful since people need to have confidence in the activists. When human rights activists become overly political, the people will see them as political activists, and views toward the state will become 100 percent dark and negative.

CHRI: Is the state’s repressive reaction to activists, including human rights lawyers, making activists more radical?

Davoudi: When I first started the “Without Retouch” channel on Telegram, it was focused on professional issues facing lawyers, but later we got into political topics. When the interrogator asked me [while I was detained] why I did this, I said, “It was your fault. When the political system prevents me from discussing matters in my profession, the deeper I investigate them, I see you’re our main problem. So, you shouldn’t be surprised if I become more political.”

For instance, I was looking into the bar association’s policies to figure out why only 5,000 or 6,000 out of a total of 20,000 or 30,000 lawyers participated in its internal elections. I concluded that the state’s many wrong policies and administrative structure were the root cause. So, I had to become political. The interrogator did not have anything to say in response to my reasoning. But later, when I thought about the things he told me, I wondered whether I could have separated human rights activities from politics.

In other words, we shouldn’t get into the kind of discourse that gives the state the upper hand. My personal experience tells me that activists who did not get into politics were able to better protect themselves from state oppression. It does not mean that they were never suppressed, but they experienced less harm compared to political activists, and they lasted longer.

CHRI: As a human rights lawyer, you have witnessed many unlawful actions and human rights violations by the judicial system toward prisoners and political prisoners accused of political crimes. What have you learned that could help activists in the struggle for human rights?

Davoudi: One of the most important issues is the security establishment and the crises they have created for the state itself. The main problem in its confrontation with civil rights activists is the lack of sincerity—treating them as if they are the enemy and agents of foreign intelligence services. It refuses to see them as part of the people. In many instances, I heard judges saying that my clients had acted against the interests of the people. My response was that, well, they are part of the same people and just because they have different opinions, you cannot exclude them.

The question is, is this how the judicial and security officials really think of these activists? The answer is no. This may have been the case in the early years after the establishment of the Islamic Republic, but in more recent times, it has only been an excuse to suppress dissent. The authorities know very well that a large segment of the population has the same objections toward the state. I would ask the judge, why do you think my client is not part of the people? This shows how the state is being insincere.

When activists are being interrogated, they insist that they are part of this society and have no ties to the enemies of the people. But their sincerity is questioned by interrogators who accuse them of trying to conceal “foreign ties.” Why? Because the authorities want to condemn them to severe sentences. In some cases, the pressures under interrogation have gone too far and caused detainees’ deaths, including Sattar Beheshti, under torture by interrogators.

The other issue is that the authorities claim that the security and political establishment have been infiltrated. Well, by whom? Yes, it could be agents from foreign intelligence services. I have seen some behavior that has made me genuinely believe that all state bodies have been infiltrated. The most recent example is how [journalist] Keyvan Samimi was harassed and transferred to different prisons and prevented from having phone contacts, but ultimately he was freed. So why did the authorities have to put so much pressure on him if they wanted to let him go? The other example is [poet and filmmaker] Baktash Abtin, whose transfer to the hospital was clearly delayed and unfortunately caused his death. My question for the authorities is, why did they think he is a serious threat? I had met him in prison and truly he was the last person you would consider a national security threat. Why should they treat writers and poets like this?

On many occasions in discussions with judicial authorities, they would concede that they are paying a heavy price for this kind of behavior toward activists, but it seemed like they had no authority to stop it. This was also true in my own case. I was a lawyer for [political prisoner] Zeynab Jalalian and gave many interviews regarding her case but I was not well-known and nobody saw me as a civil or political activist. But after I was arrested, it became a different story.

Why should there be 13 different security and intelligence agencies? It should be noted that they are not just involved in gathering intelligence, but they make arrests as well. It does not matter to them if they do it correctly or at a high cost. These agencies must separate intelligence work from operational activities. This important separation of duties has not happened in Iran and as a result, we see that imprisoned environmentalists being accused of espionage by the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps’ (IRGC) intelligence organization, but the Intelligence Ministry insists they are not [spies], thus becoming a victim of parallel operations.

CHRI: When you were given a heavy prison sentence, many international organizations reacted. Do these actions have an impact?

Davoudi: They have a lot of impact if they follow certain principles. First, they need to be impartial. Recently, Amnesty International reacted to the situation in Israel. This defuses claims by authoritarian states, such as the Islamic Republic, that these organizations are not impartial.

Secondly, these organizations should be independent of governments in countries where they are based. Recently former Tehran police chief Morteza Talaei was spotted in Canada. But we know very well that the Canadian government is not giving visas to many Iranians only because they had completed their compulsory military service in the IRGC. Human rights organizations in Canada should have reacted and held the government accountable.

The other point is that the support of human rights organizations should go beyond issuing statements. It is time to use new tactics since it seems that the Islamic Republic has become immune to that kind of support shown for activists. These human rights organizations should gather a report about the conditions in Iran and on that basis customize their support.

CHRI: How do you envision the future of the legal profession in Iran?

The state does not recognize the legal profession as a legitimate activity. In Islamic theology, there is no such thing as a lawyer, except when the prisoner has a speech impediment or is blind.

The state sees itself as Islamic and considers the legal profession a Western invention, which it wants no part of. The state would prefer that the legal profession did not exist at all. Not having the power to get rid of lawyers, they have instead given precedence to lawyers who tow the official line, through Article 48 of the Code of Criminal Procedure [which in national security cases denies prisoners the right to choose their own lawyer].

If the state does not see favorable results, it will try other methods. In fact, the state is at a point where it wants to change the legal profession into a business activity. In 2013 I wrote an article titled, “A law license is not a business permit.” It is a social contract. What the state is trying to do to lawyers is shameful.

Read this interview in Persian.

Find more of CHRI’s interviews with leading Iranian activists and thought leaders here.

Shabtabnews In this dark night, I have lost my way – Arise from a corner, oh you the star of guidance.

Shabtabnews In this dark night, I have lost my way – Arise from a corner, oh you the star of guidance.