theguardian.com – Coup 53 was heralded by critics this summer as a “powerful and authoritative” documentary “as gripping as any thriller”, and judged by historians as crucial to understanding Britain’s relationship with the Middle East.

Made over 10 years by Walter Murch, the celebrated editor of Apocalypse Now and The English Patient, in collaboration with the Anglo-Iranian director Taghi Amirani, it tells the story of covert British intervention in Iran after the second world war and stars Ralph Fiennes, left, as an MI6 spy in a reconstruction of a key incident.

The film’s fresh perspective prompted widespread positive reaction among foreign affairs journalists, including Channel 4’s news anchor Jon Snow, who called it “utterly brilliant”.

The Guide: Staying In – sign up for our home entertainment tips

Read more

But now angry complaints from some of the biggest names in British television, including the veteran documentary-maker Brian Lapping, have blocked the general release of Coup 53. They allege the film undermines their reputations by suggesting they kept government secrets when they first told the story on television in 1985 in the landmark Channel 4 series End of Empire, made by Granada TV.

Lord Puttnam, a major figure in British film history and a mentor of Amirani, spoke this weekend of his regret about the row. “I find it heartbreaking that a generation of film-makers that I revere should feel it necessary to block a wholly admirable new documentary made by a world-class team,” he said.

Baroness Kennedy has been asked to mediate between the two sets of warring documentary-makers, but negotiations have broken down. This weekend, Amirani and Murch told the Observer they now face a painful choice between a long legal battle or making expensive changes to important elements of their film in order to regain the right to use footage from End of Empire.

“In our documentary, we say how much we admired the research the Granada team had carried out back then,” said Murch. “It is very sad that audiences can no longer see our film, given the years we have spent on it and the positive response it has had for a year at film festivals.”

Amirani added that the “cover-up” he hoped to expose, and the one he refers to when promoting his film, was carried out by the British government, not by the makers of End of Empire. “The whole reason we made the film was to tell the full story of what happened in Iran,” he said. “The British government have still not officially admitted what it did.”

Lapping, whose criticisms have been backed by many of television’s leading figures, including former Channel 4 executive Liz Forgan, believes the new documentary implies his earlier coverage of the same historic events in Iran was compromised by government pressure, something he denies. “Coup 53 clearly implies that our team was leaned on by government to remove an alleged filmed interview; that End of Empire was complicit in censorship,” Lapping said. “We are consulting solicitors. We would much prefer not to go to the law. We will only do so if we do not get a positive response to our requests.”

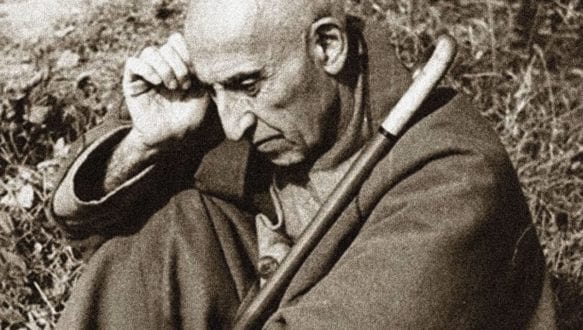

At the centre of the argument is the undisputed British secret service provocation of the Iranian coup d’etat of 1953: an attempt to unseat the country’s first democratic leader, Mohammad Mossadegh, in order to reinstate the Shah on the throne. The move was secretly desired by both Britain’s postwar government and America, as a way to ensure “stability” and secure lucrative colonial interests in Iran’s oil industry.

In 1985, researchers working for Lapping at Granada interviewed a former intelligence officer who claimed to have orchestrated the coup. Norman Darbyshire, played in Coup 53 by Fiennes, detailed exactly how his actions had been calculated to prompt unrest and ultimately led to the toppling of Mossadegh’s regime. The MI6 officer said that, as part of “Operation Boot”, he spent “vast sums of money”, well over a million and a half pounds”, adding: “I was personally giving orders and directing the street uprising.” But he does not appear in the Iranian episode of End of Empire and both Lapping and one of his main researchers, Alison Rooper, says she is sure he was not filmed and did not agree to give direct testimony.

Yet Darbyshire’s explosive evidence was recorded in a typed transcript that somehow made its way to the Observer journalist Nigel Hawkes the week before the episode was broadcast in 1985.

“They may have made a mistake in giving it to me,” said Hawkes this weekend, “but it gave lots of detail about how the coup was organised, so it was a decent story.”

Donald Trelford, then editor of the Observer, recalls the powerful story that Hawkes wrote up, quoting from Darbyshire’s account, although also indicating that the former intelligence officer would not appear on screen. “The involvement of the CIA and MI6 in the coup was widely known about by then, so that wasn’t the story. We were interested in the Darbyshire interview because it provided official confirmation of it and colourful details about M16’s dirty tricks,” he said.

No further media coverage followed the revelations, but Trelford says he believes the government did not issue a “D-notice”, an official instruction preventing publication. “We had no approach from the Foreign Office or anybody else. I was a member of the D-notice committee at the time, so I would have known.”

“I do not know who handed it over to the Observer,” said Rooper last week. “Presumably, the idea was to publicise the programme.” The picture is muddied by the fact that a CIA operative also active in the field, Stephen Meade, was interviewed on the record and filmed for End of Empire, although he also did not appear in the episode. Amirani and Murch used Meade’s archived, unseen interview in their new film and suspected that similar footage of Darbyshire might also exist.

The Darbyshire transcript was, however, later seen by the author Stephen Dorril and used in his book MI6. Rooper and Dorril both appear in Coup 53; and on screen the former Granada researcher tells Amirani and Murch she has no clear memory of what happened with Darbyshire. She and Lapping claim this creates an unfair impression and suggests they had agreed to suppress content.

In 1953, after the ousting of Mossadegh, the Shah flew back to Iran from exile in Italy and ruled until the 1979 revolution that set up the current religious regime. Darbyshire died in 1993.

Shabtabnews In this dark night, I have lost my way – Arise from a corner, oh you the star of guidance.

Shabtabnews In this dark night, I have lost my way – Arise from a corner, oh you the star of guidance.