madinamerica.com – Iran witnessed a dramatic growth in the diagnosis of Bipolar Spectrum Disorder (BSD) over the last few decades. This has been accompanied by a rise in the prescription of mood stabilizers and other drugs. A new study in Culture, Medicine, and Psychiatry investigates the conditions underlying this rise in diagnosis and the accompanying controversies.

The researchers, Fahimeh Mianji and Laurence Kirmayer of the Division of Social and Transcultural Psychiatry at McGill University, interviewed Iranian psychiatrists about the trend. Most participants reported both overdiagnosis of BSD and over-prescription of mood stabilizers. The growing influence of Western Psychiatry, including Western classification systems, the power of prominent Western experts, and pharmaceutical industry involvement were some of the noted reasons for these changes.

More importantly, participants attributed the diagnostic increase to alliances between local health systems with powerful institutions, rapidly transitioning cultural norms, and Psychiatry’s shortcomings in working with socio-ecological issues.

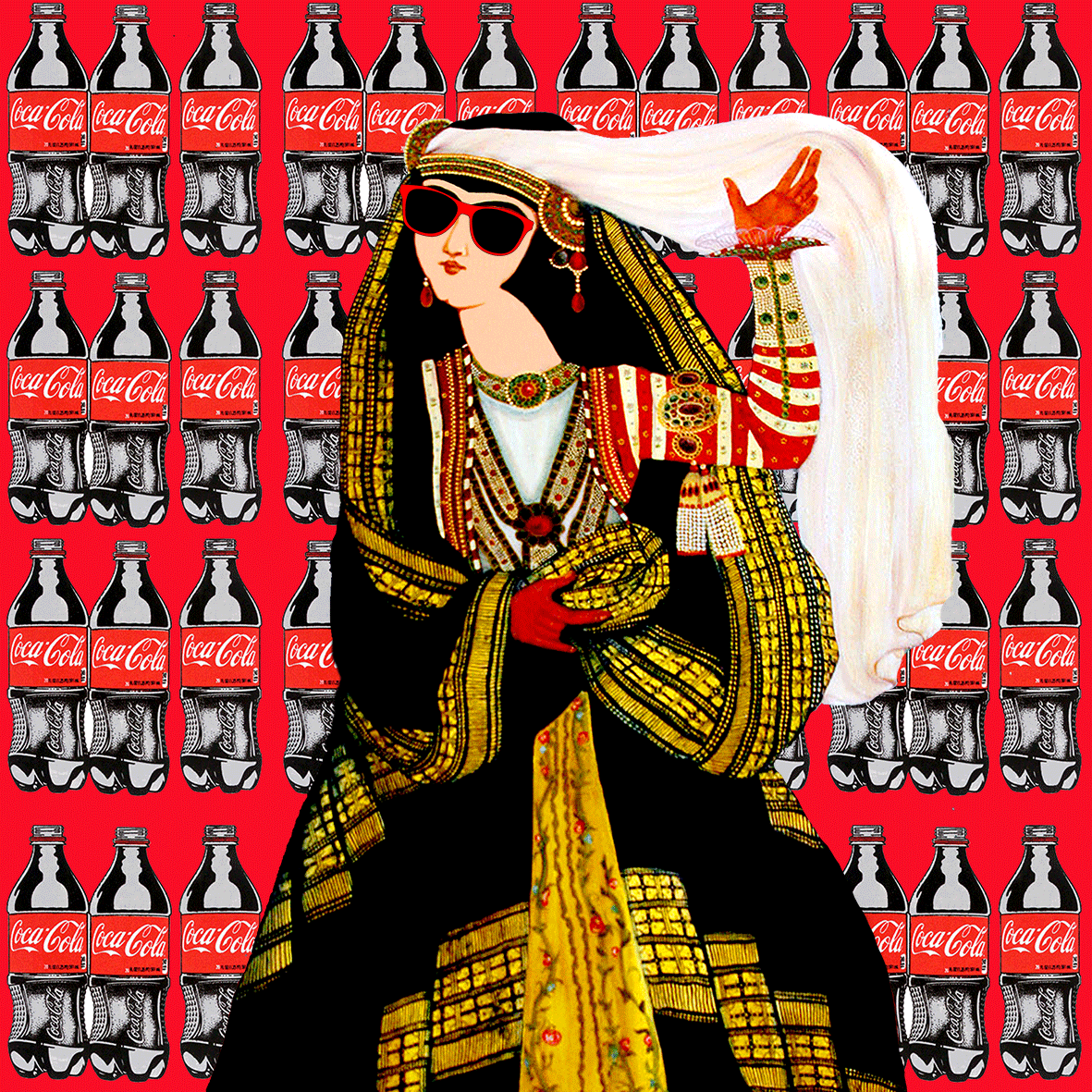

The export of Western Psychiatry is mired in controversy. It exerts immense global influence; Western psychiatrists are overrepresented in reputable conferences and academic journals and are involved in the training of psychiatrists in other countries. Critics note that biological psychiatry tends to medicalize socio-cultural problems. Others have pointed out that the discipline is based on studies conducted in the Global North and problematically exports those concepts to the Global South.

The rampant ‘biologization’ of social distress in countries like Iran and India has been well documented. In Iran, distress caused by sociopolitical problems and military conflicts was reconceptualized as depression. In India, many activists and researchers are fighting against the Global Mental Health Movement, which contains embedded assumptions that psychological suffering has biological origins and psychiatric solutions. Others have contended that Western ways of understanding the mind are being exported, and thus indigenous ways of being and knowing are getting exterminated.

In the 1990s, there was an exponential increase in the diagnosis of Bipolar Disorder, especially as diagnostic boundaries were loosened with the introduction of Bipolar Spectrum Disorder (BSD), also known as ‘soft bipolar.’ This increase reverberated throughout Iran, where many assumed they were finding bipolar patients who had previously been “hidden.” Controversy arose as others noted that the concept itself lacked validity, and its cross-cultural adaptation was problematic.

Mianji and Kirmayer interviewed 25 leading Iranian psychiatrists who specialize in mood disorders. They were asked about their understanding of BSD and their opinion on the use of this diagnosis. Thematic coding of the semi-structured interviews produced three broad themes discussed below. Additionally, archival research was carried out on popular media and publications.

The soaring numbers of BSD diagnoses were attributed to direct educational efforts of popular national psychiatrists or “opinion leaders,” translation of books on BSD from English to Farsi, and pharma-led conferences on BSD over the years. More importantly, local factors–such as valuing American cultural and scientific practices mixed with the centralization of power which discouraged diversity of opinion in academia–were also seen as contributing to this trend.

The diagnosis of BSD is a controversial one in Iran, with some psychiatrists insisting that it is over-diagnosed while others contend that it is under-diagnosed. Some participants joked that there were clinicians who somehow always found BSD. The authors write:

“Thus, a ‘bipolar-minded’ psychiatrist looks at everyone through bipolar lenses. The psychiatric residents at one department created a “Time until bipolar diagnosis” scale to measure the length of time before the first clinician in psychiatric rounds diagnoses any given patient as bipolar. Dr. N commented that it usually takes 1–2 min after the patient leaves the diagnostic interview for the psychiatrists and residents’ case discussion to settle on the bipolar diagnosis.”

Participants also mentioned specific structural factors unique to Iran, which aided in this overdiagnosis of soft bipolar. First, examination-based psychiatric training in Iran is heavily dependent on American textbooks, journals, and diagnostic systems (now the DSM-V). Since these themselves are heavily influenced by pharmaceutical intervention, indirectly, Iranian psychiatry is also affected.

Most newer psychiatrists are trained under this model of BSD, and hospital training only exposes them to the most severe cases. There is little training in psychotherapy, community mental health perspectives, and psychosocial approaches, which has led to over-prescription of mood stabilizers.

Another structural factor contributing to the overdiagnosis of soft bipolar is pharmaceutical consumerism. The absence of patent laws allows local drug manufacturers to produce globally popular drugs and advertise them to Iranian psychiatrists. This includes marketing the concept of soft bipolar and insisting that adding mood stabilizers to antidepressants has no “downside.” Similar trends where pharmaceutical companies use physician education materials to push a diagnosis and their own drugs have been observed for Binge-eating disorder.

Iranian drug companies organized symposiums where national opinion leaders encouraged the use of soft bipolar. Additionally, the repeated citing of prevalence rates of psychiatric disorder in popular media and newspapers has changed the social discourse around suffering.

One newspaper article from 2010 noted that since the prevalence rates of disorders were so high, “Psychiatrists suggest putting antidepressants in Tehran’s water.” Thus, people’s own experience of psychosocial distress is changed – reinterpreted and felt as a medical problem.

Local cultural factors also influence the popularity of drugs to solve interpersonal and psychosocial problems. These include the introduction of modern mind-body dualism, which replaced traditional Iranian understanding of mind and body as one, faith and respect accorded to physicians, pharmaceutical marketing and consumer culture, and social and familial conflict. The affordability and access to medication also contribute to some of the excessive pharmaceutical consumption; psychotherapy, on the other hand, is not covered by insurance.

The education of the public on the medicalization of everyday interpersonal conflict can be seen in the following words of a famous Iranian psychiatrist at a publicly broadcast event:

“If you have anxiety, it always has a reason, like pregnancy, marriage, etc., remember that it is normal and temporary. But I prefer that you do not even have that kind of anxiety. Before giving birth, for instance, you can treat the anxiety with tranquilizers. You can become anxiety-free before an exam. Before an important meeting with a loved one. You can cut these unnecessary anxieties… You always ask me whether exercise, prayers, alternative medicine, and things like that work; ‘anything but medication, doc,’ you say. This is a [audience laugh] polite way of insulting me because I am a doctor, and it is my job to treat you with medicine…”

Lastly, the medicalization of psychosocial problems serves the needs of specific political and religious forces that can use it to pathologize issues like homosexuality, extramarital affairs, or expression of women’s sexuality. Anything that opposes religious rules can now be attributed to a biological pathology.

Despite four decades of socio-political conflict in Iran, including globalization, revolution, and war, Psychiatry has viewed people’s suffering through the lens of ‘atypical’ behaviors – both internalizing and individualizing deeply socio-political problems. The foreign pressures and import of American nosology mixed with Iran’s own social and cultural factors have allowed many diagnoses like soft bipolar to flourish.

****

Mianji, F. & Kirmayer, L.J. (2020). The Globalization of Biological Psychiatry and the Rise of Bipolar Spectrum Disorder in Iran. Culture, Medicine, and Psychiatry, 44. 404-432. ttps://doi.org/10.1007/s11013-019-09665-2 (Link)Previous articleOverheated, then Overtreated: My 10-Day Involuntary HoldNext articleHow Mindful Awareness Can Reduce Suffering

Ayurdhi Dhar, PhDMIA Research News Team: Ayurdhi Dhar is assistant professor of psychology at Mount Mary University. She is the author of Madness and Subjectivity: A Cross-Cultural Examination of Psychosis in the West and India (to be released in September 2019). Her research interests include the relation between schizophrenia and immigration, discursive practices sustaining the concept of mental illness, and critiques of acontextual and ahistorical forms of knowledge.

Shabtabnews In this dark night, I have lost my way – Arise from a corner, oh you the star of guidance.

Shabtabnews In this dark night, I have lost my way – Arise from a corner, oh you the star of guidance.