CHRI – A recent trip by a UN special rapporteur to Iran could have been a historic moment—had she responded to an open letter by human rights activists to meet. Instead, Alena Douhan, the UN’s special rapporteur on the negative impact of the unilateral coercive measures, ignored the appeal and carried out her trip—applauded by the government in Iran—as planned.

Three months later, at least one of the activists, former political prisoner Ahmadreza Haeri, was sentenced to 3.8-years in prison for signing the letter. Douhan did not mention Haeri or discuss the government’s repressive policies and ongoing human rights violations in her report.

Seventeen years have passed since the government in Iran banned UN special rapporteurs that could be critical of state policies from entering the country, which is why Douhan’s trip, and her refusal to address the worsening human rights situation beyond the issue of sanctions, was strongly criticized.

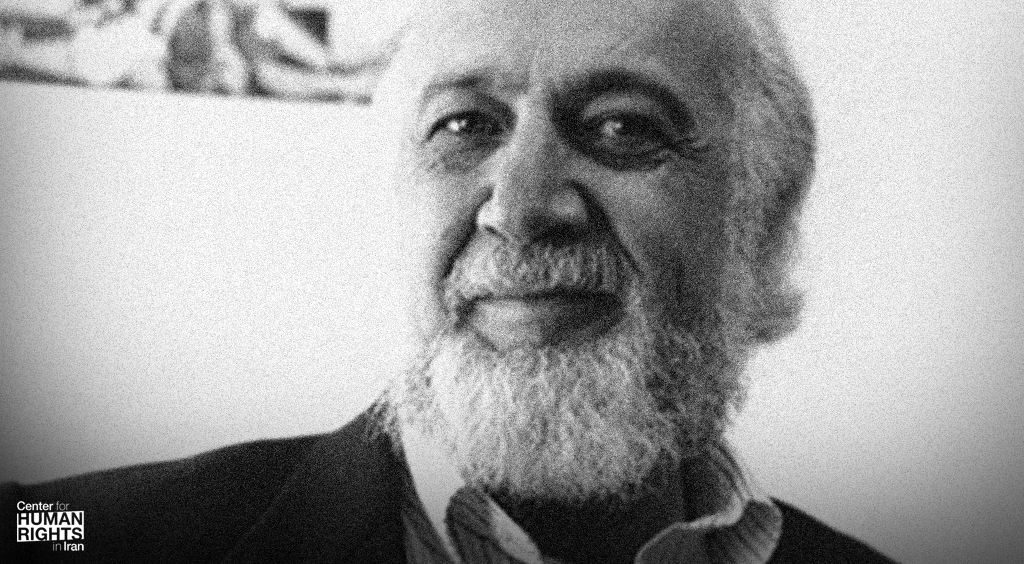

In an interview with the Center for Human Rights in Iran (CHRI), initially conducted in Persian and excerpted below, political scientist and former diplomat Mansour Farhang noted that “the Islamic Republic permitted Ms. Douhan’s entry into Iran while having a history of obstructing the work of UN special rapporteurs by refusing to allow them into the country to investigate human rights violations.”

While emphasizing that he doesn’t oppose studies on the impact of economic sanctions, he added that human rights investigations should not be solely linked to sanctions in Iran, where repression and rights violations were rampant long before they were imposed: “Ultimately, when she left, Douhan said nothing about human rights violations in Iran and instead directed all her criticism toward countries that had sanctioned Iran.”

CHRI: In a recent article titled “How Alena Douhan was deceived on human rights” you strongly criticized the UN special representative’s trip to Iran. Why do you think the UN’s approach toward Iran was flawed?

Farhang: The member states of the UN Human Rights Council rotate and some of them, like Saudi Arabia, Libya, China, and Russia, have no interest in human rights whatsoever. Then there are states like Cuba, Russia, Venezuela, and Iran that try to tie the issue of sanctions to human rights.

Countries that impose sanctions deserve criticism for the adverse humanitarian and economic impact that sanctions undoubtedly have on people’s livelihoods. But the more important issue is Alena Douhan’s appointment as a UN special rapporteur.

Ms. Douhan’s appointment was aimed at emphasizing the linkage between human rights and economic sanctions, a strategy pursued by sanctioned countries to abuse the UN mechanism.

Violations of human rights have been going on in Iran for years, even before the country came under severe international sanctions. When Mahmoud Ahmadinejad was president (2005-13), the extent of the economic sanctions was not as broad as it is today and the country’s oil revenues were at the highest levels, yet we still witnessed numerous human rights violations.

What I find very serious is the lack of reaction from the international community and human rights organizations toward Douhan’s appointment and the narrative imposed by sanctioned countries that ultimately abuse the position of the UN Human Rights Council. It is important today for the international human rights community to clearly react to this issue. I haven’t seen Amnesty International or Human Rights Watch clearly criticize the abuse of the UN mechanisms by sanctioned countries with the appointment of the likes of Ms. Douhan. This is not just about Iran, therefore the international human rights community needs to take a clear stand on this issue.

CHRI: Human rights observers and the UN special rapporteur on the situation of human rights in Iran have expressed serious concerns about the crackdown on Iran’s civil society. At the same time, Ms. Douhan refused to meet with Iranian civil society activists. What do you make of this contradiction?

Farhang: This contradiction can be explained by looking at the 40-something countries that compose the Human Rights Council. Due to the rotation of its members, sometimes the majority of countries on the council are the ones trying their hardest to undermine human rights investigations and suppress reports. Countries like Cuba, North Korea, Venezuela, and Russia are fundamentally opposed to the existence of special rapporteurs investigating human rights violations.

You saw how warmly she was welcomed by Islamic Republic officials and the great extent to which she was used as a propaganda tool on the country’s state television. She held many meetings with Iranian officials but none with civil rights advocates or politicians outside the ruling circle. Ultimately, when she left, Douhan said nothing about human rights violations in Iran and instead directed all her criticism toward countries that had sanctioned Iran.

What I want to emphasize is the abuse of UN mechanisms that allow members to limit investigations to the impact of economic sanctions. I want to be clear that I do not oppose studies on the impact of sanctions on people’s livelihoods, but only if they are carried out by economists and other experts. That would be understandable and logical. But that’s a totally separate issue from the regime’s increasingly brutal crackdown on political dissidents and civil rights activists, the rising number of prisoners of conscience, the confrontations with women, and other human rights violations.

As an adviser to Human Rights Watch for many years, I recently told them that they should pay more attention to the abuse of the Human Rights Council’s mechanisms. All international human rights organizations should take a clear stand against attempts to undermine the credibility of human rights investigations. At this juncture, Iran is a good example but not the only human rights violator that takes advantage of the UN’s human rights mechanisms and erodes their credibility.

CHRI: Do you believe that a strong stance by UN officials on this issue will have an impact on Douhan’s report on Iran?

Farhang: It will definitely have an impact if international human rights organizations take a serious and critical look at the Human Rights Council’s existing mechanisms. Unfortunately, there are still some organizations and political currents that aren’t attentive to this problem. Some of them even congratulated Douhan for going to Iran and asked her to meet with families of political prisoners, relatives of executed prisoners and civil rights activists, even though she had no intention of meeting with them. Her trip had a different goal.

What must be taken into consideration is that the Islamic Republic permitted Ms. Douhan’s entry into Iran while having a history of obstructing the work of UN special rapporteurs by refusing to allow them into the country to investigate human rights violations.

I strongly believe that human rights organizations should write to the UN High Commission for Human Rights and criticize these mechanisms because Ms. Douhan’s trip to Iran and her narrative of the sanctions had nothing to do with human rights.

CHRI: How has the Islamic Republic used Douhan for propaganda purposes?

Farhang: Ms. Douhan’s title, special rapporteur on the negative impact of the unilateral coercive measures on the enjoyment of human rights,” itself has a lot of propaganda value for the Islamic Republic because it grabs the attention of public opinion in Iran and regional countries, even though the public is not aware of how these mechanisms work. That’s why I’m so adamant about highlighting and criticizing the abuse of these mechanisms by sanctioned countries.

CHRI: Has Douhan’s stance undermined the UN’s credibility?

Farhang: This has been one of the biggest challenges facing international human rights organizations. From the very beginning, there were organizations with ties to power that wanted to hollow out human rights principles, and they still do.

The UN’s human rights endeavors have had an impact. From a historical perspective, human rights were never a discourse in countries like Iran before the [1979] revolution. Of course, there were several lawyers like Karim Lahidji who made great strides in spreading awareness about human rights, even though they didn’t succeed in forming a broad human rights organization.

Authoritarian rulers are always trying to destroy human rights organizations and impede the work of activists, but it is my belief that human rights have become a positive topic in today’s world with a lot more public awareness, especially in Iran. At the same time, we don’t see significant changes because of international human rights activities in any country in the Middle East.

As you know, the human rights situation in Egypt is almost worse than Iran’s. There are other countries in the region that have very bad human rights records. The impact of human rights activities may not always be palpable but it should be emphasized that what’s important is keeping the human rights discourse alive; a discourse totalitarian powers want to discredit. Cultivating this discourse is the most important job of human rights organizations.

Based on my life experiences and teachings on the subject of human rights, I have come to see wonderful developments in this field over a long period of time. In the U.S., developments concerning human rights and African Americans have been unprecedented. Today, many members of Congress are African Americans, which was unthinkable not too long ago. Or in France women could not vote until 1945. In the U.S., women fought for 80 years for the right to vote.

We should look at the historical trend in developments and how the activities of human rights organizations helped shape them.

CHRI: To what extent can identifying human rights issues on the local level help the UN investigation mechanisms?

Farhang: When we talk about human rights, we must look at them from two different angles: objective and emotional. In other words, someone who has lived under a system based on discrimination could theoretically understand the concept of respecting opposite views but when he is facing the issue in reality, he may not act on that belief.

Allow me to give you another example. Most Iranian thinkers and intellectuals today are in favor of equality between women and men and strongly oppose discrimination against women. But for these theoretical worldviews to translate into action and behavior requires a long time.

Imagine if we suddenly expected [traditional Iranian] culture to accept the idea of girls having boyfriends just as much as it allows for the notion of boys having girlfriends. That would be difficult, no matter how much men favor equality between women and men in today’s Iranian society. Therefore, we must always have these two aspects in mind. Many of the concepts that human rights activists have fought for blossomed over a period of many years.

CHRI: Has the human rights discourse had an impact in Iran?

Farhang: I think it is having a great impact for two reasons. First, for more than 40 years the Islamic Republic has greatly interfered in people’s lives and constantly devised new ways to violate their private space while imposing countless restrictions on their lifestyles. This has inevitably politicized a large segment of society and turned them against the ruling establishment. Second, “utopia” has disappeared as a world concept.

After 1941, leftist forces in Iran, especially the Tudeh Party, attracted many followers among the middle class but human rights were not one of their concerns. Today, on the other hand, communist and utopian ideas have disappeared. The Islamic Republic has unwittingly caused human rights concepts to become more prevalent among Iranians.

Read this interview in Persian

Shabtabnews In this dark night, I have lost my way – Arise from a corner, oh you the star of guidance.

Shabtabnews In this dark night, I have lost my way – Arise from a corner, oh you the star of guidance.