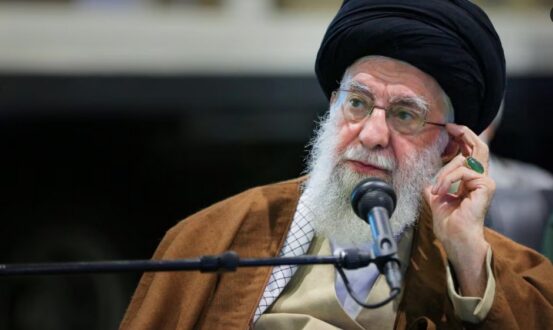

iranintl – After nearly 45 years of Ali Khamenei’s rule in Iran, the most important question for many is what will happen after his death, a smooth or a rocky transition.

Contrary to what has been presented so far in the discussion on succession after Ali Khamenei, this article will not speculate about the time of his death, the identity of his successor, power struggles between the clerics and the IRGC, or the role of China, Russia, and the West in the matter. Instead, we will delve into the decision-making process. Presenting two sets of facts concerning the background of power transfer from Khomeini to Khamenei and from Khamenei to the next leader, should the regime remain intact.

1989: Smooth Transition

After Khomeini’s death, the succession process unfolded relatively smoothly, devoid of tension, and can be attributed to five key factors. Firstly, the presence of an influential figure like Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani, who held sway among middle, left, and right-wing officials within the system, played a pivotal role. Rafsanjani was essentially a ‘kingmaker’ who not only influenced Khamenei’s ascent to power with his unverifiable narratives but also held sway over numerous pivotal institutions, from parliament and the executive branch to state media, the police force, IRGC, and the Ministry of Information.

Secondly, a five-member board comprised of Mir Hossein Mousavi, Abdul Karim Mousavi Ardebili, Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani, Ali Khamenei, and Ahmad Khomeini made critical decisions during Khomeini’s illness, exercising comprehensive control over all centers of power. This board effectively prevented marginal power centers from gaining influence, holding the reins of coercive powers after the removal of Hossein Ali Montazeri and his supporters from key positions. Montazeri had been Khamenei’s designated successor who had fallen out of favor before the leader’s death.

Among second-tier officials, there existed dozens of relatively influential figures aligned with different political factions, including Ali Meshkini, Mohammad Reza Mahdavi Kani, and Ahmad Azari Qomi on the right, and Jalaluddin Taheri, Yusuf Sanei, and Mohammad Mousavi Khoiniha on the left. Political groups were attentive to their advice, which mitigated concerns within security and military institutions regarding infighting. Additionally, only a minimal number of Islamist figures were subjected to persecution, torture, or harassment by the regime, which limited internal opposition to the new leader.

The absence of any significant social movement in the post-war period left the regime with ample latitude to designate the next leader. Consequently, both Khomeini’s funeral and the Experts Assembly session that elected Khamenei, unfolded without societal tension or challenges. While the populace might not have been content with the status quo, the absence of a sizable opposing movement or dissenting voices was notable.

Furthermore, the tranquil security and political landscape in the region after the Iran-Iraq war, combined with the relative weakening of the Iranian navy by the US in the southern waters, contributed to the smooth transition of power. There was a notable absence of perceived foreign threats to the regime.

Turbulent Transition

After Khamenei’s passing, the situation will not be as peaceful as before, as none of the five conditions mentioned earlier will apply. Instead, the opposite circumstances are in place. There is no one within Ali Khamenei’s inner circle who possesses the stature, power, and influence of Hashemi Rafsanjani, capable of assuming the role of a “king-maker.” Rafsanjani’s absence poses a greater threat to the system than his presence would have. In totalitarian systems, individuals often play a more significant role compared to institutions.

Khamenei’s close associates, such as the head of his office, the president, or the head of the Expediency Council, are more disliked among the people and political figures than Khamenei himself. Even cabinet members and lawmakers view them with disdain. The removal of Qasem Soleimani by President Donald Trump in 2020 had a considerable impact, as Soleimani could have been such a kingmaker. Even the reformists praised him for his role in advancing their agenda and did not consider him an adversary.

Khamenei has transferred power primarily to IRGC commanders but has consistently rotated them, preventing any one of them from developing significant influence. Figures like Hossein Salami, the commander of the IRGC, and Esmail Qaani, the commander of the Quds Force, are not taken seriously by most. Beyond the upper echelon, there is no alternative power center capable of leading state affairs. Various power centers on the periphery, in the form of factions and dormant assets, could be rapidly mobilized.

Former high-ranking officials have been either isolated or eliminated, losing their previous support base. They have been marginalized to the point of becoming detested by insiders. The well-know influencers within the regime are now the preachers, eulogists, and Basij members, all unpopular among the public. There is a lack of charismatic political figures.

In 2024, numerous political and social movements are active and prepared to exploit any power vacuum. Hundreds of thousands of young individuals, suppressed during the Mahsa movement, and families who have lost loved ones may take to the streets under the right conditions. However, the government has become more repressive and brutal. The next confrontation between the opposition and the government will likely result in more casualties on both sides. Society is in turmoil due to the regime’s oppression and abuses, making it unlikely for the government to rely on silence and social passivity during the succession process.

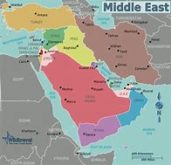

The regime’s interventions across the Middle East have led regional countries to view the Islamic Republic as a threat and welcome any domestic instability and turmoil in Iran. When Israel can remove nuclear and military officials openly and steal nuclear documents without significant repercussions, it is evident that more significant actions can be taken in a chaotic situation.

For these five reasons, there is no one to jump-start the leadership “junk car” in the event of a jurist guardian’s death, allowing the next jurist guardian to seize the steering wheel. In such a situation, those seeking control will likely have to engage in internal power struggles.

Despite the limited number of leadership candidates backed by influential factions, there are imminent violent clashes between these factions for three key reasons:

- The Expert Assembly lacks legitimacy among insiders, as it comprises low-level clerics, who have not won their seats in competitive and free elections but essentially appointed to their positions.

- There is fierce competition for the country’s resources in an environment, which has become much more corrupt since 1989.

- Apprehensions of swift elimination of opponents after a new leader is chosen, given the historical trend of the system eradicating all internal opposition in the past two decades.

Shabtabnews In this dark night, I have lost my way – Arise from a corner, oh you the star of guidance.

Shabtabnews In this dark night, I have lost my way – Arise from a corner, oh you the star of guidance.