Al-Monitor – At an initial glance, one might assume that Tehran’s paths for dealing with Washington’s reimposed sanctions all end in either Brussels or Beijing. It should be noted, however, that Iran is also working on opening other avenues — namely those leading to its neighbors.

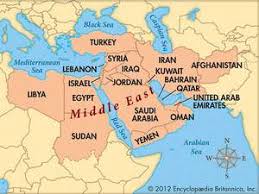

Based on recent customs’ statistics, in the first six months of the current Iranian year 1397 that began on March 21, 2018 — which coincided with the United States pulling out of the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) and reimposing sanctions on Iran — 56% of the country’s $23 billion worth of non-petroleum exports were absorbed by neighboring countries. Compared to the same period in the previous Iranian year that began in March 2017, this showed an 8% increase. More importantly, Iran’s non-oil exports to its key neighbor markets — Iraq, the United Arab Emirates and Afghanistan — jumped by 44.58, 30.03 and 30.90%, respectively. Except for Turkey, Kuwait and Turkmenistan, Iran’s exports to other neighboring countries also grew during this time.

The reimposition of US sanctions and the devaluation of the Iranian rial in the past few months has played the biggest role in boosting Iran’s exports to neighboring markets and creating this new avenue. In recent years, the impacts of the fluctuating exchange rate of the rial on exports have created an incessant debate in Iran’s political economy. While various administrations have pursued a policy known as “suppressing the [dollar’s] exchange rate” due to concerns over declining social status and consequently being defeated in elections, some economists have warned against this and called for a “more realistic exchange rate” as the most important step in increasing Iran’s exports.

With US sanctions being reimposed and the Iranian government concerned over the future of the country’s currency reserves, the outdated policy of “suppressing the exchange rate” seems to be coming to an end — of course as a result of force and not by choice. In other words, external pressures have brought this old policy to a halt. Meanwhile, with the collapse of the rial, the internal economic crisis has become prevalent. But at the same time, it led to a dramatic growth in Iran’s exports to neighboring markets.

The intensifying economic crisis has prompted Iran to make new attempts to facilitate financial interaction with its neighbors. In recent months, economic diplomacy and penetrating the markets of neighbors has become growingly important in Iran’s overall foreign policy. While presenting his plan to parliament for a vote of confidence in the Iranian year 1396 that began in March 2017), Iran’s Foreign Minister Mohammad Javad Zarif described economic diplomacy and strengthening relations with neighbors as his main priority, while emphasizing the need to export non-oil products as well as technical and engineering services. Soon afterward, the structure of the Foreign Ministry was altered to prioritize economic diplomacy, an economic deputy position was created, an economic deskwas formed in Iran’s embassies, and ambassadors were evaluated on their performance regarding economic diplomacy. In recent months, Iran has increased its efforts to expand economic exchanges with its neighbors. The Iranian parliament’s National Security and Foreign Policy Commission is a partner in these efforts and has held meetings with envoys of neighboring countries to overcome sanctions.

Additionally, Iran has tried to engage in non-dollar-based trade with its neighbors. The country’s exports to Iraq and Afghanistan, its principle neighbor markets, is mainly done through local currencies and by utilizing border towns. In the first six months of the current Iranian year, Iran’s non-oil exports to its neighbors totaled $13 billion, about $6.1 billion of which was to these two countries. In other words, half of Iran’s exports to its neighbors are done in a currency other than the dollar. In addition to this, Iran has stepped up its efforts to sign bilateral monetary agreements and use of currency swaps. A bilateral agreement reached with Turkey has already been put into effect. The initial deal was reached on the sidelines of a trilateral meeting held in Tehran and attended by Iranian, Russian and Turkish presidents in early September. The agreement calls for the use of national currencies instead of the US dollar in all oil and non-oil transactions. This agreement was further followed up by the governor of the Central Bank of Iran, Abdolreza Hemmati, during a recent trip to Russia.

The reimposition of US sanctions and the Central Bank cutting back on the dollars it is offering to economic actors and importers has also become a growing problem in Iran’s currency market. Border cities with Afghanistan and Iraq such as Herat and Sulaimaniyahhave turned into hubs for getting non-bank dollars into Iran. This “behind the scenes bazaar” is not monitored by the Iranian government. There have even been reports of $2-3 million dollars being transferred in cash daily from Afghanistan to Iran.

Iran’s tourism sector has also been affected by the recent devaluation of the rial and has become dependent on its neighbors more than ever before. The first five months of the current Iranian year saw a 45% increase in the number of foreign tourists arriving in Iranwith about 3.1 million people coming into the country. Of this number, about 2.5 million visitors were from Iraq, Azerbaijan, Turkey and Afghanistan. Significant portions of this were people who came through border towns with economic agendas. This was especially the case in the Arvand free zone, where Iran had removed visa requirements in 2017 to facilitate an economic boom, attract more investments and expand the tourism industry in the region. However, the flood of Iraqis entering this free zone has taken a toll on its infrastructure and prompted the Iranian government to reconsider putting visa regulations back in place.

Opening the path to neighbors to overcome sanctions is of course accompanied with its own challenges. Iranian officials continuously accuse Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates (UAE) of disrupting the currency system in Iran and believe the UAE has been a major contributor to the country’s economic crisis. Acting as Iran’s second trade partner and the main link between its economy and that of the world, the UAE has imposed great economic pressures on Tehran.

US sanctions have also made it difficult for Iraq and Afghanistan — two US allies who are also two of Iran’s key trade partners — to continue their economic transactions with Tehran. Iraqi Prime Minister Haider al-Abadi’s decision to not make dollar-dominated transactionswith Iran, transaction difficulties between Iran and Afghanistan, and the occasional strictness adopted by the Afghan government toward Iran are some examples.

Furthermore, the devaluation of the Iranian rial has prompted many Afghan immigrantswho were working as cheap labor in different sectors of Iran’s economy to return home. Iran has over 50 technical and engineering projects in Iraq that are half finished. With the reimposition of US sanctions, these projects will also face new difficulties — especially in terms of banking transactions. Another challenge caused by the devaluation of the rial is the smuggling of gasoline and agricultural products from Iran to neighboring markets. According to some reports, about 20 million liters of gasoline are smuggled out of Iran and into neighboring countries on a daily basis. Managing these challenges is increasingly difficult for Iran.

The US withdrawal from the JCPOA has mainly led to the creation of a complicated, multilayer crisis in Iran’s political economy. Meanwhile, the results of this crisis — along with the devaluation of the rial — have caused an increase in Iranian exports to neighboring markets. Today, Iran’s economy is entwined with that of its neighbors more than ever before. In addition to Brussels and Beijing, Tehran can somewhat look to its neighbors for dealing with the impact of sanctions.

Shabtabnews In this dark night, I have lost my way – Arise from a corner, oh you the star of guidance.

Shabtabnews In this dark night, I have lost my way – Arise from a corner, oh you the star of guidance.