Iranwire – Health workers play a critical role in society, for example by serving at the frontlines in protecting people from the covid pandemic, and this has included hundreds of Iranian Baha’i doctors and nurses. But these Iranian healthcare workers are not in Iran; instead, they live in countries around the world, treating their patients, where they are admired and praised for their efforts. The one country where they cannot work is their homeland of Iran.

Many of these doctors and nurses – some of whom studied and served in Iran – lost their jobs after the 1979 Islamic Revolution. They were expelled from the universities and their public sector jobs, barred from practicing medicine, jailed and tortured, and a considerable number of them perished on the gallows or in front of firing squads.

The crime of these Baha’i doctors, nurses and other health workers was their faith in a religion that the rulers of the Islamic Republic believe is a “deviant” faith.

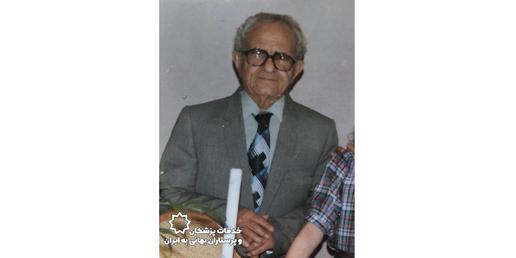

IranWire’s ongoing series about the contributions of Baha’i doctors and nurses to Iranian society, before the 1979 Islamic Revolution, now looks at the life of Jamaloddin Mostaghimi, a world-renowned anatomist and the “father of anatomy” in Iran.

Dr. Jamaloddin Mostaghimi always introduced himself as a teacher – not just as a doctor. Dr. Mostaghimi, the father of the science of anatomy in Iran, was a leading international figure in his field; eight anatomy research papers are registered under his name. He had an amazing knowledge of all parts of the human body – more than most anatomical experts. Besides Persian, he was also fluent in German, English, French and Arabic and edited editions of reputable anatomy books such as Gray’s Anatomy and Sobotta Clinical Atlas of Human Anatomy.

Dr. Mostaghimi was also a pioneer in using dissection and autopsies at Iranian universities, medical schools and hospitals, in cities including Tehran, Mashhad, Babol, Ahvaz and Urmia. And decades ago he authored the first Persian textbook on anatomy in Iran – which is still being taught today.

Jamaloddin Mostaghimi was born in 1916 in Shiraz. His original first name was Jamal but when, under Reza Shah Pahlavi, formal IDs became mandatory, the agent of the National Organization of Civil Registration came to their school and Jamal registered his name as Jamaloddin, meaning “grace of faith”. “Mostaghim”, meanwhile, meaning “upstanding”, was the title that Abdul-Baha, son of Baha’u’llah, the founder of the Baha’i faith, had bestowed on him. Jamal’s father was Mohammad Hashem who, after converting to the Baha’is faith, became known as Fazel or “learned”.

Before his conversion he was the prayer leader at Bardi Mosque in Shiraz and preached and taught at Shah Mosque. Mohammad Hashem also farmed, to make a living, because he believed that making money through his clerical role was not right thing; in this, he differed from some of his clerical colleagues.

Mohammad Hashem resigned as prayer leader at the mosque after he became a Baha’i and lived according to the Baha’i teachings – a religion which has no clergy. He was harassed for this and, later, was forced to move out of Shiraz to Abadeh, a small town in Fars province, with his family. Jamal was four years old at the time.

Mohammad Hashem, now known as Fazel, then moved to the town of Neyriz and was hired as an Arabic teacher by the Department of Education. He spent the rest of his life in that town. But Jamal was sent to Shiraz for his education and was placed in the care of his older brother. Jamal would on occasion continue to visit Neyriz to see his family.

Jamal was known to sit under a tree next Shah Cheragh Holy Shrine after school and to complete the homework of other students in exchange for a small fee. He would leave the homework in a hole in the tree for the others to collect. But even so, he had no money to buy candles to study at night; all the same, he succeeded aged 17 at passing final exams at high school.

During the exam, Abolghasem Fiuzat, head of the Education Department of Fars province, was invigilating the session when he saw Jamal take something out of his pocket. Suspecting that he was cheating, Fiuzat approached him. Jamal was in the habit of putting raisins and chickpeas in his pocket for snacking. Fiuzat saw that Jamal was not cheating ad had in fact completed the exam with correct answers to every question.

Fiuzat later invited Jamal to his office and suggested that he go to Tehran to continue his education. Universities were new to Iran at the time. Jamal said he could not afford to live in Tehran and that he was going to work at his brother’s watch repair shop after receiving his high school diploma.

A few days later, Jamal received an anonymous letter with three tomans enclosed. The letter asked Jamal to continue his studies in Tehran and that he would receive three tomans every month.

Jamal went to Tehran where, at first, he decided to attend the military academy because, besides having a place to sleep, he would be paid 30 tomans a month. Jamal was standing in the registration line at the military academy when a former classmate saw him and said: “Why do you want to become an officer? You will get killed when there is a war! Let’s go to the Teacher’s Academy and become teachers.”

Jamal was too shy to insist on his own desires and so he followed his friend to the Teacher’s Academy – although he was not happy that their salary was half of what military officers were paid. But as he lined up to join the Teacher’s Academy, yet another former classmate, by the name of Daghighi, saw him and insisted they should go together and register at the University of Tehran’s Medical School. Jamal was too embarrassed to tell his friend that he had no money and that the medical school would not subsidize his studies. Jamal Mostaghimi nevertheless became the eightieth and last student who registered at the Medical School in 1934 – its first year of operation.

Jamal needed a place to live in Tehran. But the only money he had was the three tomans he had received from the anonymous donor in Shiraz – barely enough to keep him from going hungry. He sometimes had to subsist on a single loaf of bread for a whole day.

Jamal needed more money so he looked for a job. He went to the offices of the Medical School, explained his situation, and asked for a job at the school. Dr. Abolghasem Bakhtiar, a founder of Tehran University’s Medical School, introduced Jamal to the American missionary, Dr. Edward Blair, who had been hired by the government to teach anatomy. Dr. Blair was setting up a dissection laboratory in the basement of the Medical School and was embalming cadavers. For a salary of 30 tomans a month, Jamal went to that basement every night after his classes to help Dr. Blair with the embalming process.

Dr. Blair saw Jamal’s eagerness to learn and spent extra time to teach him anatomy and dissection. Jamal became so adept that his teachers asked him to instruct other students.

Dr. Mostaghimi completed medical school and began his compulsory military service. He asked Dr. Amir Khan Amir Alam, founder of the Iranian Red Lion and Sun Society, a member of the International Red Cross, to intervene on his behalf so that he would be sent to the southeastern city of Kerman where his salary would be 65 tomans. Dr. Mostaghimi visited Dr. Amir Alam after his service, to thank him, who replied: “No thanks are necessary; instead, go to Mashhad and set up a school of medicine.” Dr. Mostaghimi accepted and set out for Mashhad in early 1941.

The early 1940s witnessed an epidemic of typhus and typhoid in Iran and Mashhad had been badly hit by the epidemic. Trachoma was another contagious disease raging in the city. Mashhad had few doctors and most people relied on traditional apothecaries and faith healers more than doctors. Anglo-Soviet forces had occupied Iran in August 1941, meanwhile, and had deposed Reza Shah Pahlavi. The Shia clergy’s power in Mashhad went mostly unchallenged as a result and they supported traditional Islamic medicine against modern medicine.

Such was the situation that the young doctor, aged just 25, found in Mashhad, with no money and little experience. Mashhad lacked the resources to build a medical school, especially with advanced laboratories or dissection facilities, so Dr. Mostaghimi and other doctors opened the Graduate Health School of Mashhad as a prelude to a full medical school. Enrolling student had to have completed the first three years of high school and would then be required to pass a final exam, after four years of training, awarding them a special certificate. Graduates were not allowed to practice medicine in places with populations over 10,000 but, after working for eight years, they could register for the fourth year of a medical school and graduate as fully qualified physicians in three years.

Dr. Mostaghimi taught anatomy at the Health School and prepared the dissection hall – though he had no budget. Following a strike by teachers and students, the government gave the school a budget, and the dissection hall became operational. But a riot in Mashhad in 1944, stoked by clerics who used their pulpits to incite the people, spread the idea that the Health School was stealing the bodies of Muslims and wantonly cutting them into pieces.

Dr. Mostaghimi and his colleagues visited several prominent Mashhad clerics to explain what their work. But the clerics were not interested. The doctord were faced with no choice, in the face of inflamed popular anger, but to close the school.

Dr. Mostaghimi then moved to the city of Kashmar in Khorasan province at the invitation of a woman who had founded a hospital in the city. He also opened his own clinic. Most of the patients who visited this clinic were impoverished: not only did Dr. Mostaghimi not charge his patients but he even gave them money to buy the medication they needed. And after a time, he returned to Mashhad.

The local clerics had calmed down and the Graduate Health School was reopened. Dr. Mostaghimi rejoined the faculty and again taught anatomy and dissection. And finally, on November 23, 1949, with the government’s approval, the Mashhad School of Medical Sciences was opened, and the Graduate Health School was closed after its final cohort graduated. Dr. Mostaghimi joined as an associate professor and was tenured in 1957; from the beginning, until 1973, he was the chair of anatomy. He also later taught at Urmia Medical School in Urmia, West Azerbaijan, and at Jondishapur University of Medical Sciences in Ahvaz, Khuzestan.

Dr. Mostaghimi also opened his own clinic, now in Mashhad, and kept it open for 25 years until he moved into he took on a full-time teaching schedule. In all those years he never asked his patients for payment – they would pay him whatever they could afford or did not pay at all.

He asked to retire in 1973 and, the next day, he went to Tehran and began teaching orthopedics to residents at Shafa Yahyaian Hospital. He also taught at Jorjani Hospital and at the Imperial Medical Center – which is today part of the University of Tehran School of Medical Sciences.

Until the 1979 Islamic Revolution in Iran, Dr. Mostaghimi was a member of the International Congress of Anatomists, which met every five years. His discoveries and advances were presented to this congress and, as a result, registered at the international level.

He registered eight research papers in anatomy, including “Proof of Lack of Communication Between the Brain’s Olfactory Bulb Nerves”, which was accepted for presentation at the Eighth International Congress of anatomists in Germany in 1965. He found two nerve fibers in the brain, “one of which goes to the frontal lobe and the other to the external capsule’. Finding and recording the deep layer of the deltoid ligament, which play an important role in memory, was one of Dr. Mostaghimi’s greatest contributions to his fioeld.

In 1947, on a scholarship, he took a course for coroners and medical examiners at the University of Edinburgh Medical School in Scotland.

After the Islamic Revolution, Dr. Mostaghimi was invited to teach at the University of Urmia, an invitation he accepted. In 1985, at the invitation of Mashhad School of Medicine, he returned to his adopted home city and, except when he traveled across Iran to give lectures, he remained there until the end of his life.

But he was never officially hired by an institution after the Revolution and, therefore, his name was not among the Baha’i academics who were fired during the so-called “Cultural Revolution” in the early 1980s. Iran also had no other anatomists at Dr. Mostaghimi’s level, and his abilities were in high demand. Even the country’s professors of anatomy were either his students or his students’ students.

And yet for some time, the Academic Jihad, the organization responsible for carrying out the “Cultural Revolution”, did not permit his book on anatomy to be reprinted because of his Baha’i faith.

Dr. Mostaghimi continued to teach at various Iranian universities as a visiting professor. In 1987, while in Yazd to inaugurate that university’s dissection hall, he was injured in a traffic accident and was forced to walk with a cane for the rest of his life. But he did not quit teaching and continued his work with the Mashhad Medical School.

In 1970, five of his students received their PhD degrees and the university also hired an American-educated doctor to manage the dissection hall. Mashhad University then decided to get rid of the Baha’i professor who helped found their medical school. The university started by making the conditions of his work inconvenient; they locked the doors to the restrooms on the floor where the dissection hall was located, so that the ageing Dr. Mostaghimi, now walking with a cane, would have to climb the stairs to use the restroom. The administration also cancelled some of Dr. Mostaghimi’s classes without telling him. He would show up to teach and find no students present – and only then did he learn that the class had been cancelled without being informed. And eventually Dr. Mostaghimi was told that his services were no longer needed.

He nevertheless found new ways to teach. He traveled to Tehran once every week until 1994 to advise PhD students and, at one point, he also taught at the University of Ardebil in northwestern Iran.

Dr. Mostaghimi also trained teachers for the new Baha’i Institute for Higher Education, or BIHE, an informal or “underground” university for Baha’i students which was founded after the Islamic Republic banned them from higher education. On September 29, 1988, security forces raided the homes and classes of BIHE teachers: Dr. Mostaghimi’s class in Tehran was one of their targets.

Dr. Jamaloddin Mostaghimi continued teaching – and learning – until the last day of his life. He was known for maintaining his habit of rising at 4am to pursue new studies. Dr. Mostaghim, a prominent Iranian doctor and educator, passed away in Mashhad on November 27, 2005, aged 90, and was buried in that city.

He could have taught at any university in the world. But despite his many challenges, especially after the Islamic Revolution, he never entertained the idea of leaving his country. He loved the Iranian people and worked for them all his life and with all his heart.

Shabtabnews In this dark night, I have lost my way – Arise from a corner, oh you the star of guidance.

Shabtabnews In this dark night, I have lost my way – Arise from a corner, oh you the star of guidance.