Iranwire – Liz Truss is the first British prime minister since the 1979 revolution not to have to deal with a thorny issue in UK-Iran relations : namely Britain’s debt to Iran for Chieftain tanks that the Shah had paid for but were not delivered after the revolution.

In fact, it was during her short tenure as Foreign Secretary that the matter was finally resolved. On the sidelines of one of the most dramatic hostage diplomacy stories of this century, Truss also had a chance to familiarize herself better than most with the Iranian regime.

It is unclear whether her premiership will mark a change of approach from Britain. In 2017, around a year and a half before he became prime minister, her predecessor Boris Johnson visited Tehran as Foreign Secretary, hoping to improve the tense relations between the two countries with an ambitious set of proposals.

But despite his announcing that he and President Rouhani had agreed Britain and Iran wanted progress “on the removal of all obstacles in the Anglo-Iranian relationship”, relations under Johnson showed no tangible signs of improvement, neither at the time nor after he became prime minister. The exit of the United States from the JCPOA, the arrest of Nazanin Zaghari-Ratcliffe and then the long coronavirus pandemic left no opportunity.

Nazanin’s imprisonment in particular cast a long shadow. In March 2022, Truss was present when that crisis was resolved earlier this year – in part because the UK paid Iran £400m for the unfulfilled tanks order.

In September 2021, early on in her career as the foreign secretary, Truss had met with Iran’s Foreign Minister Amir Abdollahian when they were both in New York to attend the UN General Assembly. It did not take long to become evident that the freedom of Nazanin Zaghari had been one of the main topics of discussions in this meeting.

On September 24, 2031, a day after the meeting with the Iranian foreign minister, Truss said: “Today marks 2,000 days since Nazanin Zaghari-Ratcliffe’s cruel separation from her family. She is going through an appalling ordeal. I pressed the Iranian foreign minister on this yesterday and will continue to press until she returns home.”

Eventually it came to be, and in March 2022, Truss was present at RAF Brize Norton near Oxford to welcome Nazanin Zaghari and Anousheh Ashoori back to the UK.

That crisis had begun during the last few weeks of David Cameron’s premiership, continued under Theresa May and lasted through the last months of the Johnson administration. Morad Tahbaz, another British-Iranian national who also holds US citizenship, is still not allowed to leave Iran.

Truss, then, is the first British prime minister since 1979 not to have the Chieftan tank debt hanging over relations. But the problems are deeper and more fundamental than that. One specific sticking point is the continued harassment of journalists working for the BBC’s Persian language service and their families.

Apart from that there is the wider issue of ideology and human rights abuses in Iran. At times, Britain at the forefront of standing up to the unacceptable behavior of the Islamic Republic – as it was recently to Vladimir Putin.

Liz Truss became familiar with the details of Islamic Republic’s unlawful and often inhumane practices when she served as British foreign secretary. In normal times the hope would be that now, as prime minister, she will put more pressure on the Iranian government over its unacceptable behavior – as it is, relations will probably not develop beyond a certain point.

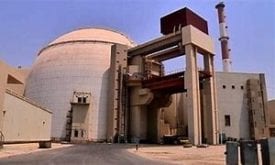

The other issue warping bilateral relations is the Islamic Republic’s nuclear program. As foreign secretary, Liz Truss showed that she was not “soft” on this issue; a year ago she warned Iran that the then-proposals on returning to the JCPOA were not going to last forever.

Britain is no longer a member of the European Union but it does continue to work closely with other European countries, including France and Germany, which are also both parties to the JCPOA.

There is also the question of impunity, and what Britain is willing to endure – a question Tehran is willing to periodically put to the test. In the immediate aftermath of 1979 the Islamic Republic could not blackmail Britain by taking its nationals hostage, as it did with other European countries, but things changed little by little after Tony Blair left office.

After him, the Iranian regime began to follow a more audacious policy without paying much of a price for it. This went so far that in 2011, during the premiership of David Cameron and while the police looked on, hundreds of Basijis attacked the British embassy and another British diplomatic compound in Tehran, ransacking offices, tearing down the Union Jack and stealing documents. They even set a small building on fire and several people were injured.

According to Ali Akbar Salehi, Iran’s foreign minister at the time, the attack ended only when the office of the Supreme Leader Ayatollah Khamenei intervened, though the British Ambassador Dominick Chilcott told the BBC that Iran was a country in which such action was taken only “with the acquiescence and the support of the state”.

Following the attack, Britain closed its embassy in Tehran and even after British diplomats returned, Foreign Secretary William Hague kept relations at the lowest diplomatic level. This situation lasted until the JCPOA was reached but then, with the arrest of Nazanin Zaghari-Ratcliffe in 2016, a new round of tense relations started.

These have not been resolved with the return of two hostages. Liz Truss has inherited relations battered by criminality on Tehran’s side and indulgence by the UK government. The outstanding issues will take the will and the determination of a real prime minister to address – if it is determined to be important enough,

Shabtabnews In this dark night, I have lost my way – Arise from a corner, oh you the star of guidance.

Shabtabnews In this dark night, I have lost my way – Arise from a corner, oh you the star of guidance.