BBC – It was an incident they were told never to talk about and for several years they heeded that warning. A group of 21 Iranian poets, writers and journalists believed they were heading to a literary conference in neighbouring Armenia in August 1996. But what should have been a routine trip turned into one of the most terrifying experiences of their lives.

They had hired a bus to drive them high up into the mountains through the mist-covered Heyran Pass, a steep and winding road that links two northern provinces in Iran. The 18-hour journey was beginning to take its toll and one-by-one the passengers drifted off to sleep. In the early hours of the morning, their slumber was abruptly interrupted with the sharp jolt of the bus accelerating hard.

The woken passengers watched on as the bus hurtled towards the edge of a cliff. Luckily for them, a well-placed boulder stood in the vehicle’s path and prevented it from plunging to the depths below.

Among the passengers was Faraj Sarkohi, a 49-year-old journalist and then editor of the progressive cultural magazine Adineh. “After the bus stopped, we got out one by one in a state of confusion. The bus driver approached us and apologised for falling asleep,” he recalls. Once they had recovered from the initial shock, the passengers and driver agreed to continue on the road.

But the perilous journey was not to end there. A few minutes later, the driver again turned the bus in the direction of the cliff, diving out of the vehicle as it approached the 1000-ft drop.

The bus was only stopped from careering over the edge again by an alert passenger who leapt into the driver’s seat and pulled up the handbrake, bringing it skidding to a halt as it headed towards the precipice. The lives of all 21 on board were saved for a second time.

The writers filed off the bus, stranded and bewildered by the turn of events. From the ground, they could see the vehicle’s nose teetering over the top of the cliff, with its front wheels in the air. Somehow, the driver had managed to escape and was nowhere in sight.

This time, Faraj knew it was a deliberate attempt to drive the bus off the cliff.

He saw a group of plainclothes security officials sitting in a car on the mountainous road, which would normally be virtually deserted at that time of night. These agents, he says, drove the literary group to their local office in a nearby town where they were detained for a day.

“They forced us to write a letter agreeing to not speak about the incident to anybody. After this, we understood that they wanted to kill us all.”

“We were shocked. We couldn’t understand this deep hate and brutality. We were so shocked that we couldn’t even talk to each other.” Details of the dramatic episode were kept behind closed doors for several years, and were only brought to light after a chain of events that unfolded in 1998.

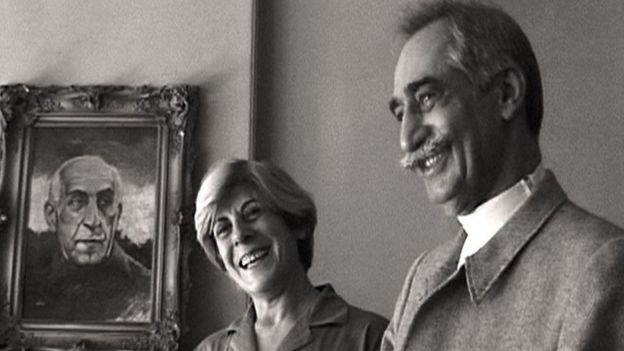

The politically active husband and wife

On a Sunday in November that year, Parastou Forouhar was sat inside her home in Germany waiting for her parents to call, as they did every week, to hear updates on family members thousands of miles away in her native Iran. She was waiting in vain.

The 36-year-old had grown increasingly anxious when she received a phone call from a BBC journalist inquiring about her parents.

“The reporter said she had seen on the telex news that they had been attacked but she could not tell me the whole truth,” she recollects.

“Afterwards I called a close friend of my parents who was living in Paris in exile and he told me that they had been killed.”

Dariush and Parvaneh Forouhar were brutally murdered in their family home in southern Tehran on 22 November 1998. Dariush, 70, was stabbed 11 times. His wife, who was 12 years his junior, had been stabbed 24 times.

Both had become outspoken critics of the authorities in Iran’s Islamic republic, and they ran a small secular opposition party which had, until now, been mainly tolerated.

The savage killing of the elderly couple shocked the nation and marked the beginning of what would soon become known as Iran’s Chain Murders.

The writer and the translator

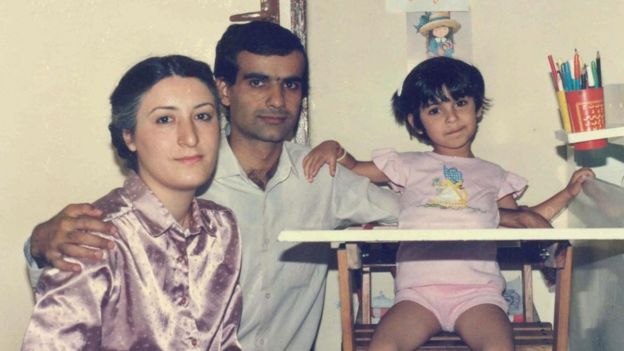

Nearly two weeks after Parastou heard the devastating news, Mohammad Mokhtari said goodbye to his 12-year-old son as he stepped outside of his house in Tehran to run some chores.

“The last memory I have of him was the moment he left our home. I asked him to buy some milk as he was standing in front of the door. But he was a little bit different, as though he felt something wasn’t quite right,” his son Sohrab, now an adult living in Germany, recalls.

Mohammad, 56, was a writer, poet and outspoken critic of press censorship in Iran. He never came home.

Sohrab’s older brother spent the next seven days searching hospitals and police stations across Tehran for his missing father. What he didn’t know was a body had already turned up at a cement factory on the outskirts of the city, a day after Mohammad’s disappearance on 3 December.

The family were not informed until a week later.

“My brother got a call from the medical authorities to come and identify his body. We were told he had no documentation or ID in his pocket, which was why they did not call sooner,” Sohrab says. According to the authorities, all that was found on Mohammad Mokhtari’s body was a piece of paper and pen. He had been strangled to death, and his body reportedly bore bruising around the neck.

On the same day the Mokhtari brothers discovered their father’s fate, a family friend and fellow writer also disappeared.

Mohammad Jafar Pouyandeh, 44, was a translator who was established in the literary world but still relatively unknown in the public eye. He was abducted outside his office in downtown Tehran in the middle of the day on 9 December.

Three days later, his body was discovered and, much like his friend, there were signs he had been strangled.

Read more stories from Iran:

- How Ahmadinejad found meaning in rap

- Iranian women threw off the hijab – what happened next?

- The ordinary Iranians finding ways to beat censorship

The deadly link

Mokhtari and Pouyandeh shared one thing in common – they belonged to the Iranian Writers’ Association (IWA), the same group that had organised the aborted bus trip to Armenia two years prior. They had been, at some point or another, openly critical of the Iranian authorities.

The association, which brought together like-minded progressive writers, poets, journalists and translators in a bid to fight censorship, had found its activities strictly curtailed under successive governments, and was banned shortly after Iran’s Islamic revolution of 1979.

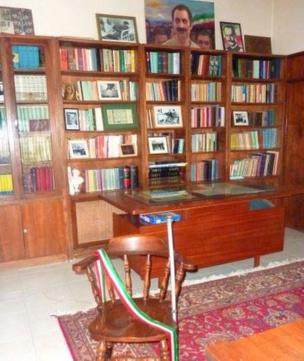

Faraj Sarkohi, who was one of the IWA’s most prominent members during the 90s, describes how they managed to bypass the ban.

“It existed because it had such a huge support. We held dinner parties to discuss our ideas behind closed doors – some were even hosted in my own house. We knew that we were being listened to but we had no other choice.”

A turning point came in 1994, when 134 members tried to breathe fresh life into the IWA by signing an open letter demanding freedom of expression in Iran. The text, which was never published in Iran, picked up a lot of support both inside and outside of the country.

Among those who helped to draft the text were Faraj, Mokhtari, Pouyandeh and several other writers who, two years later, would take the ill-fated bus journey to Armenia.

Just a few weeks before their murders in 1998, Mokhtari, Pouyandeh and four other writers were summoned to court over their efforts to stage an IWA conference. There they were interrogated and told firmly to drop their plans.

Mokhtari’s son, Sohrab, describes a climate of fear in his household growing up, and the amount of pressure members like his father were under.

“My father was threatened many times. I remember one time he got very angry at my mother after she told me this.”

“The security services controlled everything about him – they controlled his phone calls and any contact he had with other writers and intellectuals involved in fighting for freedom of expression.”

The outrage and ‘investigation’

Political assassinations were nothing new to Iran, but the savage nature of the Forouhar couple’s murders caught the public’s attention.

“What got me was the brutality of the killing – my mother was stabbed to death 24 times, and my father was killed in his study chair which was placed in the direction of Mecca in some kind of ritual killing,” says Parastou, whose parents were secularists campaigning for democracy in Iran when they were killed.

“Society in Iran was shocked and very angry. That is why there was a huge demonstration when my parents were being buried – and thousands of people came.”

People began to suspect the murders were politically motivated.

They were widely seen as part of a power struggle between Islamic hardliners who still had significant influence over the intelligence services and reformists allied to President Mohammad Khatami, whose push for greater freedom and democracy in Iran swept him to power in the summer of 1997.

Pressure began to build and in December 1998 President Khatami ordered an investigation into the killings of the Forouhars, as well as the circumstances surrounding the deaths of Mokhtari and Pouyandeh.

Just a few weeks later, in January 1999, the authorities, in a rare acknowledgement, said a number of rogue agents in the intelligence ministry had carried out the murders.

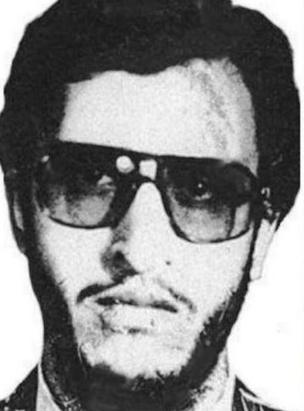

The main suspect and mastermind, they said, was a former deputy intelligence minister called Saeed Emami. He died under suspicious circumstances in custody, with officials saying he had committed suicide by swallowing a bottle of hair remover.

In total, 18 people went on trial; three people were sentenced to death (sentences that were later commuted to prison terms), two were given varying jail time and three others were acquitted.

Among those to stand trial was Khosro Barati, who later reportedly confessed to being the driver in the bus incident.

But the families of the victims rejected the investigation’s findings, believing it to be a sham. The Forouhar couple’s daughter, Parastou, and her lawyer, the Nobel Peace Prize-winning Shirin Ebadi, pored through all of the confessions.

“Each suspect said they had acted through the orders of the intelligence minister himself. This was in their confessions but the court did not follow this line, they just acted as if people would kill other people for no political reasons,” Parastou says.

The intelligence chief, Ghorbanali Dorri-Najafabadi, resigned over the case but always denied any involvement.

A series of videotapes leaked several years later appeared to show violence being used against some of the suspects to force them into giving confessions.

In the meantime, several investigative journalists started digging into the case and found links to other, unsolved and mysterious killings of intellectuals and writers dating back to the late 1980s through a variety of means, including choking, stabbing and even injections of potassium to stimulate heart attacks.

One of them, Akbar Ganji, was imprisoned for five years after publishing a series of stories pointing the finger at a high level minister in the previous government, as well as some senior clerics. None of these claims were ever investigated by the Iranian state, and most of the killings remain unsolved.

Fellow journalist Faraj Sarkohi says he considers himself lucky to have survived the ill-fated bus journey. He has, though, remained a target. Not long after the bus incident, he was kidnapped by the Iranian secret service and only managed to avoid a death sentence after the interventions of the international community. He now lives in self-imposed exile in Germany.

For Sohrab, whose father was killed before he had even reached his teens, the loss was “the end of the world”.

“I couldn’t really understand what had happened – I didn’t know anything about life or death at that age.”

Parastou is now an award-winning artist who still resides in Germany but returns to Tehran every autumn to pay tribute to her parents. She says the authorities have often blocked her and other relatives of victims from holding these memorials.

“It is now 20 years on, and the memory is still alive, as is the wish for justice and due process.”

Additional reporting from Niki Mahjoub

Shabtabnews In this dark night, I have lost my way – Arise from a corner, oh you the star of guidance.

Shabtabnews In this dark night, I have lost my way – Arise from a corner, oh you the star of guidance.