Al-Monitor – It was a cold winter day in February 2011. Nineteen months had passed since the emergence of the Green Movement amid the disputed 2009 presidential election, and the leaders of the Islamic Republic’s media centers had gathered for a meeting. One prominent producer in the room, a captain in the Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps (IRGC), bluntly said to his colleagues, “The youngest generation in our country doesn’t understand our religious language anymore. We’re wasting our time with the things we make. They don’t care about it. That’s why so many of them were in the streets protesting against our system.”

The Green Movement, the largest mass demonstrations in Iran since the 1979 Revolution, shook the political and military elite in the Islamic Republic to its core. Over my decade of fieldwork in Iran with the regime’s cultural producers (2005-2015), commanders in the IRGC continuously debated how they would close the fissures the Green Movement exposed among Iranians — and between the state and society. Gradually, they chose nationalism as a unifying force to define the Islamic Republic and to rebrand the Guards following their suppression of the Green Movement.

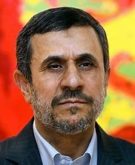

In that meeting, the IRGC’s media producers began to discuss how they had been observing an increasing trend in displays of nationalism in the general population. From the apparent spike in pre-Islamic Persian names for babies, to the large flags along highways and bridges that became a mainstay of the 2005-13 presidency of Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, and the ever-present farvahar — a symbol of Zoroastrianism, which predates Islam — the IRGC sensed an opportunity. Although nationalistic sentiments were evident in cultural production in the Islamic Republic in the 1980s and 1990s, what is now evident is an effort in many sectors of the regime to promote “Iranian-ness” above and beyond mere “Islamic-ness.”

“People are tired of us only showing them images of pious men who fought for this country. It’s our own fault for producing that kind of propaganda. Young people no longer respond to it, so we have to find another way,” one IRGC commander said to his colleagues in the February 2011 gathering.

As international pressures against Iran increased, including stifling sanctions and an intensified proxy war with Saudi Arabia, the sense of nationalism continued to rise in the country. Regime media-makers began to consciously highlight this sentiment in all their cultural productions after the Green Movement. Although this strategy began in some regime media circles before 2009, it has exponentially intensified since the suppression of the Green Movement. Today, the crescendo of this nationalist turn in the Islamic Republic is clear for all to see.

Today, the crescendo of this nationalist turn in the Islamic Republic is clear for all to see.

Among the most prominent examples of this turn to nationalism is the multimillion-dollar Sacred Defense Garden and Museum in northern Tehran, which opened in late 2012. One of the main exhibits displays large maps that show the Persian Empire ruling swaths of Asia over 3,000 years ago. It juxtaposes this map against shrinking Iranian territory throughout the centuries. Iran’s size today is minuscule in comparison with the glorified empire painted on the wall. The message of the museum is clear: Past monarchs ceded territory, thinking more about their own pockets than the nation. It was only the Islamic Republic that defended Iran’s borders, and by extension, its dignity as an ancient civilization.

The museum presents a different narrative of the 1980-88 Iran-Iraq War from the older, more traditional martyrs’ museums that dot every city and town in the country. In an attempt to gain more visitors, it has invited independent artists to make installations with nationalist themes to them, consciously welcoming those it pushed away for many years.

Yet acknowledging that this museum can only reach a limited number of people, regime media creators began to advocate for the production of music videos, in the hopes of making their message of unity under the IRGC go viral via social media.

The first major endeavor along these lines was “Nuclear Energy,” released the day before the signing of the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action in July 2015. Featuring the rapper Amir Tataloo, the video features sailors on a warship singing, “This is our absolute right, to have an armed Persian Gulf.” Tataloo, who had to produce his music underground just a year before the release of the video, had been arrested in December 2013 for his alleged cooperation with foreign satellite stations. The Iranian military’s participation in a music video with an underground artist who flaunts his tattoos and piercings appeared to be a conundrum to viewers. But, in fact, it was a strategy that could be observed among the regime’s cultural producers for the past decade.

Howzeh Honari, the country’s biggest cultural center, operating under the auspices of the supreme leader, last year released Iran’s most expensive music video to date: “We Are Standing Until the Last Drop of Blood.” The seven-minute video took over two years to make and involved a 150-person crew at a cost of $385,000.

The video tells the story of the US Navy’s downing of an Iran Air passenger plane in the Persian Gulf in 1988. Set in a town on the shores of the water, the inhabitants are seen experiencing death and destruction as a US missile rips into the jetliner. The singer, with a close-cut beard and scarf worn in the style of young Basiji men, emerges onto the beach. He is joined by a group of multiethnic and multiracial Iranian men who grab large Iranian flags, stand in unison, and march toward the US warship, singing, “Like Kaveh’s flag … I am the heir to Rostam, I am the master of Rakhsh,” referring to famed poet Ferdowsi’s thousand-year-old “Book of Kings,” the epic of the Persianate world. Kaveh refers to a blacksmith who leads an uprising against an evil foreign tyrant to reinstate Iranian rule. The connection between the defenders of ancient Persia and the warriors of the Islamic Republic is deliberate and clear. The song’s lyrics do not include any references to Islam, drawing an intentional linkage between a particular understanding of Iran and its current protectors.

These new works are not fringe expressions accepted by the regime but rather the results of a deliberate strategy pursued by regime cultural producers. This strategy moves away from simply celebrating martyrs to offering a narrative heavy on nationalism, dignity and pride. In this vein, a now common refrain promoted in memes and on Instagram as well as other social media is an appreciation of the Guards for keeping Iran safe from outside forces.

The new wave of nationalist sentiment is neither happenstance nor the sole result of outside threats such as the Islamic State, the rhetoric of US President Donald Trump or the heated rivalry with Saudi Arabia. Instead, the renewed nationalism is the result of years of work by regime media-makers designed to rebrand the IRGC as no longer a force of the Islamic Republic, but one that defends the Iranian nation. Whether this will last remains to be seen.

Dr. Narges Bajoghli is a socio-cultural anthropologist. She is a postdoctoral research associate in international and public affairs at the Watson Institute at Brown University. Her focus is on Iran, media, war and revolution. Her research has been supported by national grants from the Social Science Research Council, the National Science Foundation (awarded/declined), The Wenner Gren Foundation for Anthropological Research and the American Institute of Iranian Studies. She has directed a documentary film, “The Skin That Burns,” on chemical warfare survivors in Iran. In addition to her academic writing, Narges has also written for The New York Times Magazine, The Guardian, The Washington Post, Al-Monitor, Middle East Research and Information Project, The Huffington Post and LobeLog. She has also appeared as a guest commentator on Iranian politics on DemocracyNow!, NPR, BBC WorldService, PBS NewsHour, BBC Persian and HuffPost Live.

Shabtabnews In this dark night, I have lost my way – Arise from a corner, oh you the star of guidance.

Shabtabnews In this dark night, I have lost my way – Arise from a corner, oh you the star of guidance.